Blog

Navigating the Longtail in Internet Marketing

Self-publishers must embrace the long tail to find their niche and connect with dedicated readers.

If you are marketing your self-published book, understanding the long tail concept is like discovering how gears in a clock track time.

Imagine walking through a market that stretches beyond the horizon, where every stall offers something unique. The first stalls you see are the largest and loudest, manned by the most popular authors. Your stall, on the other hand, is way out in the distance, further than you can see, where you eagerly await a customer to come walking by. Will they ever?

This is the digital marketplace, and the long tail is its most intriguing secret. The more you understand the long tail, the greater your appreciation for SEO (Search Engine Optimization) will become.

What is the Long Tail?

Originally a term from the business world, the long tail in self-publishing refers to the plethora of niche genres and topics that, when combined, can equal or surpass the market share of bestsellers. This means authors no longer need to chase mainstream success to find their audience; there's a space for every unique voice.

Amazon maintains a catalog of 32.8 million titles. That’s a lot of books! What is seen and what sells represents an absolutely tiny fraction of their total catalog. What sells is at the head of the curve; what languishes in obscurity is in the tail of the curve.

As a new or self-published author, your book lives in the tail of the curve.

Why it Matters

The long tail strategy empowers authors by highlighting the importance of niche markets. Those catering to specific interests can stand out in a sea of millions of books. This approach benefits both authors, who can write about what they truly love, and readers, who can find books that resonate on a personal level.

Your job is to move your products up to the head of the curve through SEO, marketing, likes, recommendations, shares, good product reviews, and promotions.

Sounds expensive. It is. So how do you do this?

Leveraging the Long Tail

The long tail strategy for self-publishing authors involves identifying and targeting readers in specific niches. You must find an audience that traditional publishers have difficulty reaching.

The right niche aligns with your interests and expertise while having strong market demand. This builds authority and attracts your ideal readers from knowing your audience.

That might mean writing for a narrowly defined genre.

Authors can connect with their ideal readership by utilizing targeted marketing strategies like SEO and social media engagement.

Embracing the long tail in self-publishing opens up a world of possibilities for authors and enriches the literary landscape with diverse voices and stories. It's a testament to the power of the internet to connect writers with readers, no matter how specialized their interests may be.

The Internet makes this process easier than ever.

R

Cats and Oranges

On Oranges

Years ago, my wife and I attended a theater show where oranges were rolled onto a stage during a live performance. The actors, still thoroughly engaged in the story — dancing, moving, repeating their lines — struggled to avoid slipping on the oranges. Some, in fact, did, and when it happened, I burst out in laughter. I couldn’t help myself.

Well, my outburst wasn’t well received. Most of the audience turned to glare at me as if I was some Neanderthal who didn’t appreciate good art.

I use this story to illustrate the problem of art. A rolling orange can be one person’s serious artistic statement and another’s comedic moment. Art is entirely subjective, and what constitutes artistic expression isn’t up to us, but the judgment of our audience.

In the art of writing, we use the tools of our craft to relay a story to a reader.

We have nouns and verbs, adjectives and adverbs; we have intensifiers and modifiers. We have punctuation, sentence structure, and paragraph sequences. We have tools like flashbacks and flash-forwards. We have perspectives like 1st and 3rd person. We might tell more than show. We might have a story of one word, a hundred words, or a hundred thousand words. We strive for eloquence and brevity in our expression and, for some, capture universal themes of the human experience in our writing.

Oranges are our art. How well tell a story is the subjective choice we make as authors to relay how we feel it should be told. When someone judges our writing and experiences our art, they see it through a lens of their own personal experiences and biases. They might not like nor prefer the tools we used to tell it and may score us poorly. If anything, poor use of oranges may diminish our credibility in the eyes of readers, judges, and publishers.

On Cats

Cats, on the other hand. Everybody likes cats. People are obsessed with cats. People share cat pictures all day long. People love cats.

Cats are the bread and circus of writing — they’re stories readers want to read. A cat is what a reader expects when they read your story. Whether or not it’s a horror, romance, or adventure, readers have certain expectations about what that story should feel like. The major scenes. The characters. The action.

I often use the phrase “writing a good cat.” People must be attracted to the story to read it. They must want to pet and cuddle with the story, scratch behind its ears, feel good with it, and ultimately share it with others.

As a writer, my ability to “write a good cat” relates to telling a good story, regardless of the oranges I might have used to tell it.

On Writing Contests

In traditional publishing, we want to write stories with a good balance of oranges and cats.

Our oranges establish credibility with readers and publishers, and our cats compel our publishers to keep buying our stories, and readers to keep reading our stories.

Writing contests, however, are different.

Some contests are more cats than oranges; some are more oranges than cats.

In my opinion, peer-based contests like Writing Battle require a cat-heavy story to be successful. Stories must meet genre and connect with a broad audience of amateur writers. They don’t put as much weight in the oranges we use to tell the story; readers want a good cat. If you fail to tell a good cat, regardless of how beautiful your oranges, it will fail.

On the other hand, prestigious amateur contests like NYC Midnight and GlobeSoup require more orange-heavy stories to be successful. These are contests judged by more seasoned, if not professional, writers, not amateurs. The stories that win these contests must pass a litmus test on how those judges perceive the art. It doesn’t matter how astounding your cat is. You might write a very compelling and attractive story, but if the oranges don’t line up with the expectations of the judges, you will fail.

How You Can Tell

In my opinion, you can tell what a contest is like by reading their past winners.

Orange-heavy contests will showcase slow, dull, prodding stories on typical themes that are expertly told. No risks are taken, and there’s no excitement in the story — it’s all very bland and predictable — we’re bored, as readers, because we’ve read these stories before. But that’s what the judges expected, so it’s what the writer wrote.

On the other hand, stories (art) that are more exciting, out of the box, and fun to read, enjoyed by many regardless of technique, that take risks on art, are more cat-heavy. They’re the surprise hit experts didn’t expect, or, when we read them, may completely disregard traditional oranges. They’re stories that resonate with people, regardless of the tools and techniques used to tell them.

On Cats and Oranges

If we’re writing for contests, we generally have to write a good cat stuffed with oranges, or, as the picture above suggests, a good orangey cat. The story itself has to be compelling and meet the reader’s expectations, and our use of the art must not distract from the story or penalize it.

Now, in my opinion, some writers might gravitate towards one or the other.

Authors might struggle to win peer-based competitions but may excel in writing a predictable story well. They’ll shun the erratic, unpredictable nature of these contests and declare them “not real writing contests.” They’ll upturn their nose and go to where they’re appreciated.

On the other hand, the creative writer who fails in a structured, oranges-heavy contest may be so frustrated by the judges’ gatekeeping that they vow never to pay the $30 entry fee again and go home. They might even pack it in as a writer and give up.

The trick, I think, is found in adapting to the expectations of the contest and being mindful of both problems. At the end of the day, I think most writers would agree that cats and oranges make for better writing. We have to write strong, relatable stories, that people want to hold in their laps, and to do that, we often have to take risks and use our tools in ways that are exciting. Unpredictable. Even if they don’t meet the formal expectations of a literary judge.

Who is Ginny Greenhill?

Ginny Greenhill is a Ranger of the Aevalorn Wilds, sworn to protect halflings and aid others in finding their way.

I write her as bubbly, gregarious, and fearless. An excellent tracker who fights hand-to-hand with a bo stick, Ginny is young, idealistic, and loyal to the enigmatic Circle.

Ginny is a sidekick to Kindle Muckwalker — a lively bonfire to his mucky gloom — but unlike Kindle, she leans on using Druid Magic. She’s also pretty good with a lockpick. Her adventures center around protecting the hamlets, people, and creatures of the Aevalorn Wilds.

She made her first appearance in The Magnificent Maron Maloney.

Who is Benzie Fernbottom

Benzie appeared alongside Elina Hogsbreath in A Thyme of Trouble. As Thyme was Elina’s first story, they’ve been a team since the beginning.

I write him as an overly-enthusiastic, young, naive, helpful, yet inadvertently troublemaking sidekick.

A lightfoot, young, fit, and thin - admittedly too thin by halfling standards - Benzie Fernbottom prefers to keep his chestnut-colored hair disheveled and untrimmed, his pointed ears poking out along the sides. He has thick eyebrows, a sharper nose than most, and an eager, wide smile that would give a stranger the impression he was up to something. He wears a white collared, button-up shirt with a handsome brown and green vest and matching pants cut at his knees. And like all halflings, Benzie didn’t wear shoes - he goes through the world barefoot.

Benzie is what I’d refer to as a typical halfling. I see him as good-intentioned and kind but flawed, sometimes going to extremes.

He lives a life of service in the Parishes; he’s happy and comfortable and will never leave.

I use Benzie as a way of expressing typical halfling attitudes and opinions in an environment exposed to outside ideas - the inn, the Swindle & Swine.

He might not appear in every one of Elina’s stories, but I do try to mention him or point out where he may otherwise be.

Author’s Note: Soso

Around Mar 27, 2023, I wrote Soso in response to a Reedsy prompt to write a story about someone who says, “I feel alive.” The larger writing contest was related to spring in Japan. And happily, Soso was shortlisted! Yay!

In this story, Soso is a 400-year-old tortle, an anthropomorphized tortoise. He’s an artificer - an inventor - who makes astoundingly perfect automatons in the shape of toys. Soso is a toymaker who loves his toys and the spirit of childhood.

Soso is growing old, and I elude that he must leave for the places where tortles go to die - to the south, I wrote, beyond Shae Tahrane - because it’s warmer there. Shae Tahrane is to the south of the Aevalorn setting, and I picture it as closer to the equator. Mountains. Deserts. Savanahs. I mentioned Shae Tahrane before in The Magnificent Maron Maloney.

If Soso leaves, he’s concerned a mysterious organization known as The League will come and snatch his toys and learn how to improve upon their own automatons and craft better war machines.

Therefore, Soso sent the crow, Thomas, to fetch a halfling artificer, Artemis Teafellow. I actually pictured Soso dispatching Thomas before he started his hibernation in the fall, and Thomas had to fly out to the Parishes to track down Artemis. Eventually, Thomas found him, and Thomas had been hanging around Artemis in Ehrendvale for months. And when the time approached to leave, Thomas convinced Artemis to make a month-long trek into the mountains.

Soso’s plan is to gift all of his toys to Artemis before he leaves so that the League can’t find them.

There are some elements of this story that attempt to address the prompt:

The cherry blossom trees are a direct reference to spring in Japan.

The Zen-like koans offered by Thomas.

The origin of Soso comes from an artificer non-player character (NPC) that I created for a D&D campaign that I ran in 2022. This version of Soso is much older and varied a bit from my NPC, but the spirit is there.

At the end of the story, I reveal that Thomas the Crow is actually an extremely sophisticated toy. I pictured the automaton so perfect that its consciousness ascended to a higher understanding. Thus, Thomas speaks in Zen-like koans.

Unfortunately, as traveling with a Zen Master seemed uncomfortable, Soso erased his memory engrams to make Thomas a better traveling companion, resetting its hundreds of years of existence in a flash. I was accused of “killing” Thomas by a reader, but I perceived it as “resetting” Thomas. It’s just a toy, right? Meh, I’ll leave that one up to the reader. :)

What I loved hearing from readers is how much Soso reminded them of being a kid or playing with toys. Yay - it totally makes my day - that’s exactly what I want to hear! That’s the whole concept for Artemis.

Soso is Artemis’ origin story and attempts to explain why he has so many completed automatons and his fascination with toys. Artemis will gather up all of Soso’s toys and notes and take them to Ehrendvale in the Aevalorn Parishes. Foiled, the League will show up at Soso’s place to find nothing of value and eventually learn where the toys went, putting a target on his back! Uh-oh.

If you’re curious, I’ve drafted an outline of Artemis’ first novella, and we’ll see him again maybe eight months after Soso. I hope to have that project finished before fall 2023! Woot!

Who is Artemis Teafellow?

Artemis “Arty” Teafellow is a young Halfling Artificer who uses his tinkering skills to create and repair toys.

I picture him as having brass goggles atop a mess of walnut brown hair, a red scarf, a waistcoat, and a blue buccaneer jacket.

I originally wrote Artemis in the story Soso in March 2023. In that story, the great toymaker, Soso the Tortle, gave Arty a cache of complicated clockwork toys so he could keep them out of the hands of a mysterious organization called The League. Using Soso’s inventions, Arty explores and gets involved in things he really shouldn’t be getting into.

Arty is a young halfling with little life experience. He is fascinated by the magic of clockwork. I picture him as kind-hearted but naive, seeing the world as a kind of machine that operates off predictable rules. It doesn’t, of course, and he’s often flat-footed, making wrong assumptions.

His stories will involve steampunk and artificer (inventor) themes, dashed with maybe a little bit of Jules Verne, with a distant antagonist, The League, and what they represent.

Memories in Amber

Date: Friday, March 3, 2023

Competition: Australian Writer’s Center Furious Fiction

Max Words: 500

Criteria: Must include the concept of a CHAIR; the words ALBUM, BRIGHT, and CLICK; a character who has to make a CHOICE between two things.

The fire raged to cast a hazy, bright orange hue into the midnight sky above the river gorge. Nearby stands of pine trees were consumed by licking columns of flame, creating an inferno that filled the air with a thick layer of black smoke, causing Gisela's raw throat to burn.

“Stay here, Erika!” Gisela screamed, throwing herself out of the Jeep. On the passenger-side seat, Jinx, Erika’s Maine Coon, hissed from her cat carrier, while from behind, a neighbor’s car ladened with suitcases and garbage bags of worldly possessions raced by.

“Mom! You can’t go in there!” Erika cried, grasping at her from the back seat.

“I said, stay here!” Gisela growled, slamming the Jeep’s door to rush toward the garage. Gisela could see the skeletons of homes engulfed in a blazing holocaust only six lots down.

Bursting in, her kitchen was pitch black, and she stumbled to spill a stack of cleaned dishes, sending them crashing to the floor.

Rushing into her living room, Gisela frantically shoved rows of books from their shelving to grasp her grandmother’s album. It was a massive tome, bound in Moroccan leather and stitched with hemp cord, and weighed over fifty pounds. The woman had fled Konigsberg in January 1945, and its contents contained a century of family pictures and relics.

The heavy smoke suffocated and burned Gisela’s lungs. Gisela wheezed, struggling to breathe; she keeled in a deep cough, bracing her arm against the bookshelf. Recovering, she cradled the bulky album and lumbered to her bedroom. Throwing the album onto the bed, she rifled through her jewelry collection.

Glancing through the window, she saw the rooves of her neighbor’s on fire and the blustering, roiling wind kicking up a storm of debris and embers. Coughing, gasping for air, Gisela grunted and shoved her jewelry cabinet to the floor to tear open a dresser and rummage through its contents.

When her fingers felt the tiny shards, she grasped the necklace just a thunderous crash brought a flaming beam onto her bed. Fumes and hot ash burned Gisela’s eyes, and, shielding her head from the heat, she saw the ceiling was caving. Lunging for the book, she painfully recoiled; her fingertips burned as she reached for the album. Coughing into the crook of her elbow, Gisela turned and fled to exit her home through the front door.

Dashing to the Jeep, she swung the driver door open and dove inside.

“Here,” Gisela coughed, tossing the necklace at Erika.

“Mom?!” Erika asked, puzzled, examining the necklace. “Why?”

Clicking her seatbelt, she threw the vehicle into reverse and sped out of the driveway. Jostled, Jinx growled.

“She made it from amber found on the shores of the Baltic Sea after she left Konigsberg,” Gisela barked, throwing the Jeep into drive. Gritting her teeth, she spat, “She survived by fleeing the Russian army. I’ll be damned if it won’t survive this.”

And slamming her foot to the floor, the Jeep peeled away on the road.

Author’s Note: The Magnificent Maron Maloney

Over the last week, I wrote a 12k-word novelette responding to four Reedsy prompts, all about cats. I’d wanted to write a cross-posted story across their prompts for a while, and it seemed like a perfect opportunity to bring it up.

The story’s origins come from a 2017 D&D campaign where I created a showman villain that went about the countryside transforming children into animals. As the animals with the intellect of children were easier to control than regular animals, he could train them without a great deal of hassle. Eventually, the players would catch on to the ruse and need to fight Maron to free the children.

When I originally wrote him, I imagined him as something akin to the Child Catcher in Chitty Chitty Bang Bang. In this retelling, he’s an archetypal villain, even with the waxed handlebar mustache. He’d go around to various towns and small villages, lure children to his cart of splendors, and feed them a potion that’d turn them into an animal - the first animal that came to mind when they sipped the potion. That’s pretty much who he is here, too, except in this story, he indirectly captures children and directly transforms an adult drunkard.

I think of him as a failed alchemist and a mediocre wizard. The one thing he could make well was something like a permanent polymorph potion, and the spells he had were primarily defensive spells; Gaseous Form, Expeditious Retreat, and so on. The idea was to make him slippery and difficult to pin down during gameplay. When he escaped the party's clutches, he’d no sooner show up again in another town, and the party would have to try and capture him again. There were at least three separate incidents where the party ran into him before actually killing him.

In this story, Maron’s motivations are unclear, but he’s foiled by Benzie Fernbottom, a character I introduced A Thyme of Trouble as a side-kick to Elina Hogsbreath. That tradition continues in this work where Benzie works for Elina at the Swindle & Swine and discovers something completely wrong with Maron’s animals. Benzie tries to tell people about it, notably Elina, but he’s dismissed, mostly because people are too busy and enamored with Maron. Luckily, Elina provides some kitchen magic to help reveal the truth, and combat scenes are led by Kindle Muckwalker.

This was Kindle’s first written fight scene. I imagine Kindle as a haggard, blunt halfling, a bit like Norman Reedus’ Daryl Dixon of The Walking Dead. Complementing him was a druid named Ginny Greenhill, a D&D character I made for a quick campaign at an RPG con in 2018. I saw Ginny and Kindle working together as a team, he being the muscle and she providing support. I think it played well given the word constraints, but I would like to draw out the conflict to add more richness in later editions of the story.

At the end of the story, I have Maron’s psyche consumed by a flumph, for I saw the flumph as really humoring Maron and taking advantage of his wagon to see the world outside of the Underdark. I really like the idea of a spooky visage of Maron Maloney with this tentacled creature with eye stalks sitting atop his head, wandering the dark forest, essentially sightseeing on top of a mental zombie.

The flumph is an imaginative creature and nearly a joke in D&D as a whole. I saw the flumph as an opportunity to suggest that it was Maron’s first attraction, his only real animal, and when it didn’t draw the crowds, he added children transformed into animals. The flumph uses Maron as much as Maron uses it so that it can feed on emotion and explore the world. But it’s also a wonderous possibility, a weird unbelievable thing that we want to touch, and it kind of speaks to the premise of the story. In the end, it wanders, traveling the world in wonder, seeing things for the first time. Do you remember what that was like?

A big part of this story is the power of imagination and how, as working adults, we’re often caught up in the moment and we aren’t open to possibilities. Benzie believes the animals are more than what they seem and senses a danger, yet his intuitive ideas are ignored, risking everything. Kids are like that. They see something at the moment and bring our attention to it, but we’re quick to dismiss them. If halflings are analogous to children, then Benzie is our 7-year-old, tugging at our pants, trying to get us to pay attention to what they’re experiencing.

At the end of the story, I make some big reveals about transformed people, and I specifically carved out Kimchi, an orange cat that was the favorite of Maron Maloney’s. First, I wanted to instill a wonder of who she was and where did she go. Second, I wanted to keep the character for myself; the idea of a sentient cat roaming around the Swindle & Swine causing grief for Elina was just too good to pass up.

The commercial re-write of the story will likely span 20k+ words and include more depth into the characters and the events. There was only so much I could put on the page with a 3,000-word limitation.

The story is a cautionary tale: we ignore our intuition and our imagination at our peril. If we stay too rooted in our working world and fail to listen to our hearts, then we’ll end up in a place we don’t want to be. I thoroughly enjoyed writing it an hope that I didn’t piss off the Reedsy judges for cross-posting as 12k-word story. :)

As always, thanks for reading, and thanks for sticking around.

R

Author’s Note: Return to Me

This week, I wrote a response to a Reedsy Weekly short story competition entitled Return to Me where the prompt read:

“Write a story within a story within a ...”

At first, and I’ll be honest, I wasn’t very enamored with the concept. I had no real experience writing Matryoshka-like, nested stories, and the prompt grained against my brand. I feel my style is more direct, opting toward linear narratives that can be easily consumed and digested. I hate twisting up a story like a pretzel because it meets an artistic aesthetic. Why make something more convoluted than it had to be?

Further, I didn’t feel I could write a compelling nested story in under 3,000 words. My usual model for a story this size would be three acts in 1,000-word blocks, but this story called for maybe twice the number of acts and quick transitions between scenes. I had to insert a device to transition the reader between scenes without disrupting the flow of the story.

On the one hand, I was turned off by the prompt, thinking it’d be too much work for the reward. Yet on another, it was a cool technical challenge from an accomplished short story author, Erik Harper Klass. Thinking on it, if I were taking a creative writing course, would I turn down the opportunity to try a new technique? Nah! I’d try to do the work. So I hopped to it.

Researching these types of stories, I decided on the wolfhound as a transitionary device for the reader. When the wolfhound appeared in the narrative, I signaled that we had moved on to another scene.

The beginning of the story is actually four segments in. We encounter my antagonist, Rof Mok, attending a funeral service for a fallen soldier, Wen Fak. Before that, we met Rof as a desperate thief, looting a grave near the Temple of Silvanus in Mumling. Rof Mok sins, stealing from the dead, and is rewarded by encountering the wolfhound.

The hound is a grim - an omen - that conveys a curse. Throughout the story, the grim haunts Rof Mok, driving him mad and to a point where suicide becomes his only option to escape it, taking us right back to the opening scene with Bartram.

Grims are old folklore. Grims are guardians and defend a church from those who’d commit sacrilege against it; they often take the form of black dogs. In the past, black dogs were even buried under the cornerstone of a church so that their spirit would guard the grounds. I took some license with the legend conveying a curse that followed Rof Mok around.

The nested story needed a more sympathetic/empathetic flavor to contrast against the cautionary, spooky folklore. I used the trope of a reflecting widow to weave the second story in. Reflecting on a story allowed me to stay in the past and build a foundation for Sae Fak’s backstory. I wanted to get the reader to like Wen Fak and feel sadness/empathy for Sae so that returning the ring to Wen meant something to the reader.

So what I wanted from the story was a little sweet and sour: a love story nested within a darker, more ominous one. When I read this story aloud to my beta team, I found that everyone would get really tuned in during the love story and brace for the ending. The circular movements of the story with its transitions also forced me to pause a little while reading it, and I felt it took longer to read. A more winding trail, I think, rather than a direct route, and the mind seemed to play with it well.

Thinking about transitions in that way was, in itself, a good experience and another tool in my writer’s kit. I really liked how the story turned out. I’ll definitely use it again. Bartram Humblefoot played a good protagonist to my villain and fit right in with Wen Fak’s story.

In this story, I mention that Bartram’s 66 years old, and I foresee this story taking place a few years earlier than The Murkwode Reaving.

Some “Behind Baseball” Details:

Wen Fak is actually the name of a Mumling NPC Fighter used in my D&D campaign. The original Wen Fak was an 80-year-old veteran that kept rolling nat-20’s and saving the party’s bacon. He was truly an awesome NPC. Wen Fak eventually died, eaten by a giant frog; I didn’t want to have to explain giant frogs in this story, and comedy wasn’t what I was going for, so I went with goblins. After I wrote the story, I shared it with all my players. They loved it and thought it was a fitting tribute.

I was going to write a grim into The Grotesque of Silvanus when I prepared its commercial version. That story also takes place at the same temple. I probably still will.

Mumling is mentioned in several of my works but most notably in The Murkwode Reaving. Bartram is a military commander for a Gaelwyn (human) city-state - Mumling - and the contention between his role as an officer and his religious calling is explored in that work.

In the story, I mention Brigantia, and in The Blood of the Catacomb Captive, I explored Brigantia’s wealth inequality due to its silver mines.

As always, thanks for reading, and thanks for sticking around.

R

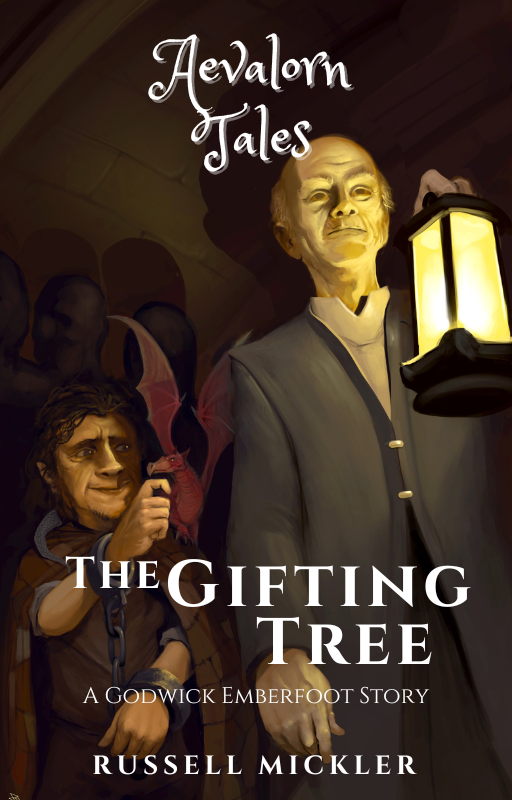

Who is Godwick Emberfoot

Godwick Emberfoot is a Halfling Warlock enslaved to the Archfae Aurusel, the Great Gardener.

There’s a lot to parse in that sentence. A warlock is a person who has made a pact with an otherworldly being. The magic he wields is gifted by their power. His pact is one of the chain: he’s subservient to his patron and soul-slaved. When I describe Godwick, he’s shackled at his wrists with a chain that runs between them.

His patron is the Archfae Aurusel. An Archfae is a powerful creature with the influence, understanding, and power to bend the Faewild to its will. The Faewild is a parallel plane where the fae live, typified by magic, chaos, and change. Aurusel maintains a garden in the Faewild and is a powerful creature in his own right.

Godwick is in possession of a magic item that I call a patchwork cloak. It’s nothing special - I imagine it as a dingy patchwork quilt made into a cloak with a hood. Its special power, though, allows Godwick to plane shift, to move between different planes of existence at will.

I see Godwick as a haggard soul teetering on the edge of sanity. He somehow came in possession of the patchwork cloak and wandered into Aurusel’s garden in the Faewild. He wasn’t outright destroyed, but rather enslaved, for Aurusel has work for a plane-shifting halfling. Being enslaved by a powerful otherworldly force and bouncing around between planes of existence rattles the mind, and his is stretched too thin.

Godwick’s face is marred with deep wrinkles and crevices, sullen eyes, and weathered skin. Inky-black, greasy hair, that runs to his back. His use of pact magic wears on his body. I perceive some of his halflingness as eroded in some way.

A part of Godwick’s pact magic allows him to find a familiar, a magicked spiritual companion. Godwick’s familiar is the pseudodragon Greymalken. Greymalken is a twist on Shakespeare’s Graymalkin, an old female cat, a witch’s familiar, mentioned in the opening of Macbeth.

The first story I wrote for Godwick was his connecting origin story to Greymalken entitled Bargains with Dragons.

Godwick is my answer to several characters that I’ve enjoyed in fantasy and science fiction. He wears a multicolored patchwork cloak. This is a reference to Joseph and the Amazing Technicolor Dreamcoat and a comic book character named Shade the Changing Man. He’s also, absolutely, a John Constantine type of character.

His stories will be fantastical, traveling to strange places, and meeting otherworldly creatures in the Faewild.

What is the Difference Between the Commercial and Non-Commercial Versions of my Work?

I wanted to take a moment to explain the difference between my commercial work and my non-commercial work.

I use Inkitt, Reedsy, and other sites as a staging area for my draft work and serialized fiction. When I post something there, it’s usually a draft and isn’t entirely cleaned up. I put it on these sites to gain visibility and get feedback from my beta readers.

I’ll revise the work until I feel like it’s reasonably presentable and then close the project out on the non-commercial site. And I leave it there so I can attract new readers who might be interested in my work.

Meanwhile, if I decide to take a project through a commercial channel (Apple Books, Amazon Books, and Google Books), I’ll walk through another round of editing to clean it up and make it suitable for people paying for something.

I’ll also usually change or extend the work to differentiate it from the non-commercial. I’ll often revise the work for clarity, add more content to the story, and change the ending somehow.

The idea is to, chiefly, spread the good word about halflings and Aevalorn Tales. I’d love to have everyone in the world reading my fun stories about halflings.

And so for those with the means and who would like to support me, I offer my commercial work.

A couple of thoughts here:

I’ll never be Stephen King. I can’t write a single title and have millions of people buy it. So I can’t write a single book and call it good. I have to write a lot to even be seen.

I’ll never retire from my writing. I do this for fun. If people pick up my commercial work, it’s like pennies were thrown into my busking hat.

I want everyone to read my stuff. Really, it’s true, and I don’t want money to be an obstacle. I mean, here, have a book. That’s what I’m all about.

Plus, I always offer my commercial work through raw files available for cheap-cheap-cheap on the website.

Anyway, there we go, and thanks for reading!

R

Author’s Notes: The Garden of Reflection

I wrote this story in response to a Reedsy prompt concerning a character that wants to disappear and does.

I wanted to draw from the idea when a person contracts a chronic disease or a terminal illness, how they might feel like a burden or inconvenience to others - how they might want to disappear.

My first thought was to make a ghost story with my bard character, Joliver Barleywood. As I started outlining, I didn’t want to trivialize the subject and felt I needed to go deeper. Jayleigh Warmhollow was a better fit; she’s my character for more complex and emotional themes.

I thought the gorgon slant was a perfect fit. It’s difficult to imagine a life where you couldn’t interact with people you love without the risk of “infecting” them.

The entry into the story takes the reader into an aftermath. The villagers tried to burn their town to destroy Uriah. The mood is deliberately bleak and sullen, and when we meet Jayleigh, she’s prepared for combat, to do whatever is necessary to restore a balance to nature.

Mythology isn’t kind to gorgons. We usually encounter them when they’re grown up, resentful, angry, and evil. They’re usually a protagonist who ends up losing their snake-ridden head. The reader’s rooting for it, of course, because we don’t want to see our brave protagonist turned to stone. That’s not how I wanted this story to end.

In this story, I wanted my reader to see Uriah as innocent: she was the victim of an unfortunate circumstance, a disease. She didn’t deserve to get her head stuffed in a bag. Instead, how can we treat someone like this with dignity?

Jayleigh wants to bargain with the gorgon and find an alternative to killing her. Like anyone who survives a chronic illness would tell you, living is harder than dying, so maybe, for some, death is a preferred option. Most in our society don’t have the option to die gracefully and on their own terms; ten states plus the DOC have “right-to-die” laws. In forty other states, the ideal value of life trumps the prolonged suffering of an individual, especially when it’d be more merciful to simply end it. When I have Jayleigh spin around and confront the townsfolk in this story, I’m really yelling at “people” who don’t have any say in Uriah’s suffering.

In the story, death always remained an option in the form of Jayleigh’s sickle. Scythes and sickles have a direct association with death, but it’s also a reference to a D&D constraint where druids can use limited forms of bladed weapons. A sickle is one.

That said, I wanted Uriah to have more options than death. Isolation is a common theme with gorgons given their curse, but I think it’s also something that the chronically ill experience. Some people withdraw from their social connections either through choice or circumstance. I felt that experience would imbitter Uriah and make her resentful; a life of loneliness was no life at all. I made a reference to Uriah as being a “baby gorgon”, like, she’s “young” and not set in her ways. Her mind hasn’t “eroded” into madness and she was still pliable. I think this is also true for people suffering from illness. Instilling hope is important to a treatment plan. Hope, in this case, was a life shared with other people, a community, that could accept her for what she was.

The Galeb Duhr is a race in D&D with a long history in the game. They’re neutral creatures and 5e even points out that they’re disposed to working with druids. Given their immunity to petrification and thousands of years of lifespan, I felt they’d make a suitable “family of choice” for a gorgon if she chose it. They offered a way out that we don’t see in mythology.

With Jayleigh’s mask, I deviated from D&D’s rules but I imagined it as something like a True Seeing spell woven into an ordinary mask. It was a convenient tool for both Jayleigh and Uriah.

I think the underpinning message is that all chronically ill have their own agency. As powerless as they might feel, they get to choose for themselves what they want out of the life they’re handed.

Author’s Notes: The Keening Cup

On Tuesday, January 3, 2023, I published The Keening Cup to Wattpad.

I wrote this story in response to a Reedsy Writing Prompt:

“Your character always makes the same promise: to change. Will they finally make it happen this time?”

This story takes place in Pondaroak in the Aevalorn Parishes, with Elina Hogsbreath at the Swindle & Swine.

Keening is the act of wailing in grief over a dead person. Wailing women figure prominently in Celtic mythology and certainly have a place in the Swindle.

I borrowed the concept of a banshee - a spirit that heralds the death of a family member - and tied it to a blackthorn wood cup.

Blackthorn trees are common throughout the British Isles and are viewed in Wicca tradition as being a trickster shrub; some Celtic lore assigns negative, sinister properties to the tree. This is the second time I wrote in a blackthorn to symbolize a sinister space or item; the first time was in The Murkwode Reaving.

I introduced a vain, attention-grubbing halfling, Horwich Cobbleberry, who uses a cursed cup to garner attention from fellow townsfolk. Horwich (Horry, he’s an attention whore, get it?), promises Elina every year that he’ll stop using the cup, and it’s a promise that he makes every year.

Horwich isn’t too difficult to imagine as an individual. People who brashly tempt fate, thinking they’ll never be harmed? Or without the foresight to see how others might be harmed by their own actions? Horwich isn’t too complicated and is probably someone we’d find in a bar on New Year’s Eve.

A part of the story is the idea of New Year celebrations. What if you could know if you were to die in the next year? Would you want to know? Would you dare to know? That’s kind of the crux of the story, where Horry is playing a double-dog dare every year.

The story’s theme is about irrational brashness that can lead to despair. Why do we tempt fate? Why do we risk knowing something we’d be better off not knowing? What’s the allure of celebrating people who are reckless with our own safety? Like, stepping into a car knowing the guy driving is intoxicated. Why do we encourage it, and why are we so accepting of their risk?

I start the story at the ending, where Elina’s digging a hole to bury the cursed cup. I thought that would make a good wrap on the story after I sent Horwich bounding into the forest.

When Elina enters her kitchen, she reviews a list of hallucinogenic herbs and psychoactive plants (belladonna, mandrake, sumac, poke root), and the astute reader gets the impression that she’s preparing reagents to create a hallucinatory effect. One of my advance readers actually burst out loud laughing after reading what I was up to in the story.

So Elina appears to be sabotaging Cobbleberry’s big moment, but she’s not sociopathic. Hopefully, I project to the reader that she’s just kind of done with the promises and wants to end the cup’s influence in her inn, once and for all. She doesn’t want to hurt Horwich, but he’s got to be taught a lesson so the yearly ritual can be brought to an end.

In my attempt to show Elina really cares about him, she reminds Horwich where to find a bullaun and to help himself. In another Celtic tradition, a bullaun is a cure or curse stone where its waters are magical.

So, is the Keening Cup really enchanted? What the banshee real or just a hallucination? I think that’s part of the story's charm where I really don’t need to say - the reader can make up their own mind.

I’ll tell you the idea of a cursed cup buried out back the Swindle & Swine is very appealing. I wonder what else is buried out there? Sounds like the stuff of a new story.

As always, thanks for reading, and thanks for sticking around. :)

R

5 Things I Avoid as a Fantasy Author

I have opinions.

This is one of my “get off my lawn” rants, so it carries a tone. I’ll apologize in advance.

Readers who follow my writing might notice that I tend to avoid certain tropes.

I avoid them because I find their presence in the fantasy genre as boneheaded, redundant, and dull.

Here at the five things that I try to avoid in my stories.

DRAGONS

Dragon tears, dragon blood, dragon venom, dragon people, dragon genes, dragon teeth, dragon gems, dragon wings, eyes of a dragon, dragon riders, blah blah blah.

If you think about it, a dragon is an apex being with no rival. Aside from others of its kind, just a clutch of dragons would decimate an ecosystem. The brood would have to spread out to find enough food to eat or gold to horde, so really, dragons shouldn’t be depicted as coexisting with nature but ravaging it. They’re an enemy of nature. If we’re to find a dragon, we should expect to find a barren countryside with all of its natural resources expended. After they’d consume everything, then they just fly right off and move to another until the fantasy world the author so diligently built is just mud and slag.

So unless the author places the dragon into a bleak wasteland where it’s consumed everything, why read the book? And even then, what’s there to write about because their species is dying. Perhaps if we zoomed-in on the moment when the last dragon inhaled its last breath so that nature could recover from the massive devastation it caused. Now there’s a good story!

The moment I start reading a fantasy book with a dragon in it, I get skeptical. I’m really tired of giant, anatomically-impossible, flying lizards with magical powers. Aren’t you?

ELVES

Groan. I’m so sick of elves.

They’re like Superman in the DC Universe.

Is there nothing that can stop them short of this super rare mineral that’s remarkably abundant on Earth?

In every respect, elves are so far superior to mankind that they should be a dominant species and enslave man (a la, “The Fey”, Kristine Rusch).

What’s this “friendship” between an evolutionary superior species and a bunch of lesser wanna-be’s? Did we see Homo Sapien and the Neandertal “get along”, go on quests together, have a pint of ale at the nearby tavern? No! Homo Sapiens came in with their larger brain and beat the smaller brains out of the neandertal if they didn’t outright fornicate with them to make them part of the “family”.

Elves are ridiculously overpowered critters. They’re so overpowered that, in the context of writing about them, their culture, art, scholarship, and instruments of war have no comparison. There are no threats, so, like Superman, you have to throw gods at them to create a conflict.

When you write about elves, you might as well be writing about demigods. In fact, in my writing, I do regard elves as demigods, and I don’t necessarily incorporate them into principal characters. The moment I introduce an elf protagonist, they’d steal the show; they have no flaws. They don’t even die appropriately. They, like, board a boat to go the east rather than just simply dying and decaying, like the rest of us.

Ugh! Elves! Really?

ROMANCE

I am so sick and tired of seeing “best selling” books capitalize on hyper-sexualized supernatural (read: werewolf or vampire) BDSM dominatrixes.

Further, why does the female protagonist, to be interesting, need to be something fantastic? Like, chosen to breed? A mistress? Part alien? Or own a “reverse harem”?

Can’t we conceive of a female protagonist with no special powers who doesn’t have an “off-the-rails” libido? Or desperate to find their one true love at the expense of living their own damned life? Who is simply a woman and a person all at the same time?

I’m also very sick of romance, as a genre, spilling into fantasy and eroding the search algorithms. If you’re going to write a romance, put it on a cruise ship with a bald captain and be done with it. Every romance everywhere should simply be on the Love Boat. Get out of my magical forests with bugbears, halflings, and unicorns; they don’t get a flip about your emotional needs.

I don’t write romance - I write fantasy! I want to escape reality, not lament about how bad my own love life is, and pine over the unobtainable.

USELESS DESCRIPTIONS

One of the biggest annoyances that I have about modern fiction is the outright need to explain things in seven pages that would take one paragraph.

I’m lookin’ at you Robert Jordan and George R. R. Martin!

When you write about a meadow, you should say, “The protagonist entered a meadow,” not provide seven pages of description about the meadow since it has no bearing on the outcome of the story! It’s just filler! It’s like, how many ways can you say that the character entered a meadow? Just one! “The character entered a meadow!”

Same for food. Hey, I like to spend a few paragraphs explaining food in my work, true, but do we need a history of each meal to be offered as some rationale by the author as to why it’s being served? Do I need to know where the potatoes came from, who they were cultivated by, and how they were yanked out of the ground? No! “Baked potatoes were on the table, and they were hot.” That’s all you need to say!

What’s funny about this is that I’ve always joked that my own novels would actually be about 10 pages long. The protagonist thinks this, does that, stabs this person, celebrates, end of story. I guess this is why I write short stories. Why take seven pages to describe something? I don’t get it. And it’s boring. Stop it!

MONARCHIES

Kingdoms… cringe. I’m so sick of kings. And their doms.

Why must a monarchy govern everything? Why is there a singular guy (usually white) in charge all things? And everybody answers to him?

I mean, why not have a perfectly acceptable fantasy setting that’s ruled by a council of old women? Or how about if people shake potato bugs in a jar to make decisions? Or, looking at indigenous cultures, are there committees or groups or people who make complex decisions over lifetimes? Certainly, in a fantasy setting, we can do better than monarchies.

I really like the potato bugs in a jar governance style. I think I’ll try using that.

Anyway, there’s my rant. Thanks for reading!

R

Author’s Note: The Murkwode Reaving

On Thursday November 24, 2022, I published The Murkwode Reaving on Wattpad.

So the title is fantastical and archaic.

The Murkwode comes from the Scottish word murk combined with the old English word for wood, wode.

Tolkien already did the Mirkwood, so I couldn’t do that, and the video game, The Elder Scrolls, did Murkwood. Still, I wanted my own “murky woods.”

Reaving is a very old word that most would recognize from the Scottish word “reive”; present participle of “reave”, which is also Old English: to rob, raid, steal, plunder.

I try to pair these concepts explored in the narrative, like trespass, to try to build the larger idea: this is a story where my heroes work their way through an old wood to plunder a grave.

My goals for this project were to:

Write a 12,000-word gritty action and adventure story involving a soldier with PTSD.

Feature Bartram Humblefoot.

Relate Bartram’s Paladin ordination.

The antagonist would be Confessor Bog.

The moral would be that you can’t take anything for granted; anything important needs to be earned.

The final draft of the work landed around 16,500 words. So that worked out.

Readers of my work would recognize Confessor Bog as the antagonist in The Ballad of Skyer Dannon, but the Ballad took place 400 years before the events in this story, and Confessor Bog was burned alive. How’d there be anything left? And that’s where the wraith and wight elements of the story came from. I needed a way to explain Bog's presence, which fit nicely. Readers would also recognize the way Bog died and his vestments; I liked the cross-over.

When I started, I knew I would kill off one of the three soldiers accompanying Bartram. I first thought it’d be Rab. But after working with the second episode, I thought I could do more with Rab while he was alive and have it contribute to the moral. I made up Platt’s backstory on the fly and found that it could also work with the project's overall theme.

I try to bring faith into Bartram’s stories; this story was no exception. That and a little bit of magic addressed the PTSD issues and spoke to the larger moral.

This work probably isn’t for everybody. It contains some challenging themes surrounding PTSD, adult language, graphic gore, and medieval violence.

I think the reception’s been good; rankings after three weeks:

There are a lot of D&D elements in the work that would attract the gamer to the story.

They’d notice the Paladin’s capabilities, the Oath of the Ancients and its abilities, the monster’s capabilities, some of the spells, and the constraints explored in the combat sequences.

I think non-gamers would appreciate the story for its action and grit, and its attempt to make something bigger out of the story.

This story is about the importance of earning something.

You just can’t be a great fighter overnight, like in Rab’s case; Platt worked for five years to earn his place in society; Bartram had to earn a lasting peace by heading into the Murkwode. Nothing’s handed to you. And doing the work is hard, and it takes time; the journey will put blisters on your hands or calluses on your feet.

It was very fun to write! I’ve been wanting to do an exciting Bartram story for a while.

Why I Write Short Stories and Novellas

Generally, I write short stories (<5000 words) and novellas (10,000 - 40,000) words.

Why? A couple of reasons.

First, rewriting a novel is a disheartening slog, and I use the term ‘rewriting’ intentionally: it’s a project that never ends. It’s a toil. For some, it can consume upwards of two years, and really, novels can languish for decades and never get done.

The prospect of endlessly working on just one endless project ticks me off. I’d much rather work on something with a definitive start and a definitive end, and even if I reworked it, it’d take a month, not a year. That just makes me feel happier.

Second, people wrote novels because it was the form expected by traditional publishers. As I recently wrote, modern books are electronically published, reproduced, and distributed at zero incremental cost. It doesn’t matter if my work is 300 words or 30,000 words: I can distribute both exactly the same way for free.

So who cares?

Finally, I think there’s a transition happening with consumer preferences and books. The very act of reading is changing. Few people are reading, and when they do read, they’re reading in shorter bursts of time. They’re reading on mobile electronic devices with smaller screens, like tablets and phones, where they can control the flow, typesetting, and introduction of new content. Bursts of reading activity with smaller samples, like, 2,000 words, benefit the serialization of fiction, where consumers are digesting reading as they would a series from Netflix. They’ll read one 2,000-word episode and return to the new episode later, or if they’ve time, binge 2-4 episodes at a time, not paying for an entire premium price of a novel, but instead paying for what they use/consume. I feel I’m writing in a format desired by modern consumers, perhaps at the exclusion of older consumers who prefer to own (rather than lease) thick, chunky novels at premium prices.

Generally, I write around 5,000 words a week so I can usually get through at least one book project a month. You know, there’s something comforting about starting a project and finishing it. Isn’t that what all writers really want? To play with an idea, build it out, and then move on to the next great thing?

Again, that idea just makes me happy. And if you write and bury yourself for two or more years in a writing project that just erodes your soul, I just don’t understand: why would you do that?

You don’t need to. Not anymore.

R

Dumbria

In my work, Dumbria is a two-parter.

In its first act, Dumbria appears as a slaver City State of Gaelwyn ran by a handful of wealthy corrupt families held together by religious fanaticism. That was 400 years prior to the current time wherein I base most of my stories.

Dumbria is the home of Bog the Confessor, a surprise villain in The Balland of Skyer Dannon; Bog the Confessor also makes a return appearance in The Murkwode Reaving as a wraith.

Dumbria got its wealth through slave labor, digging out the granite, limestone, and other materials used by all of the City States in Gaelwyn to construct their towers, castles, walls, and cities. Dumbrian ore, metals, and stone was the fabric from which Gaelwyn was built. They built their city right on top of a quarry that extends into the Wych, and they’d ship either upstream or downstream. Tons of money, lots of slave labor, lots of corruption.

However, somewhere between here and there, the slavers were overthrown and a more traditional form of governance was introduced, and, in its second act, Dumbria became a free City State.

I see this city as being stacked on top of each other in a used-up quarry, where most of the city exists in mineshafts and tunnels. It’s a port city, and conducts trade with other Gaelwyn City States, but it’s a shady bunch. Dumbria, to me, is a seat of villainy. Elements of its past still linger and are difficult to purge.

Auchenshuggle

Don’t you just like saying it? I do!

When I was trying to think of a name for a smaller hamlet that’d come under the sway of a wizard, this quasi-Germanic thing popped into my head. So I featured it in The Knave of Nodderton.

Auchenshuggle is the hamlet that Gammond Brandyford works to save against a wrathwizard incursion.

A protectorate of Nodderton, Auchenshuggle exists as a river trading town along the Wych with maybe 2,000 people. It’s a small town, a hamlet, ruled by the Rendaldo family for generations.

Mumling

When I was writing down Bartram’s backstory, I said that he was an officer in Mumling’s Army. That’s it - that’s how it was created.

At that time, I knew that Mumling was going to be a City State but I had no idea what the place would be out.

Over time, I’ve been able to add more depth to this city in various stories - The Grotesque of Silvanus and The Murkwode Reaving - as well as through fleshing out my own D&D campaign setting.

Mumling is a human City State of Gaelwyn with a population around 16,000. As Mumling isn’t along the Wych, I see them as agrarian farmers and deeply religious, connected to nature where Silvanus is the dominant deity. They’re very connected to nature and are also quite cognizant of man’s propensity towards greed, villainy, and corruption.

I don’t see the City States of Mumling or Nodderton as friends. I think they kind of resent each other. I may play that out in future work.

I see the place as kind of gloomy, dominated by elder oak trees, where humans have erected temples to Silvanus with spooky gothic architecture.

Mumling is also close to the Murkwode, a foresty-swampy flood plain that borders the Wych on the opposite side of some goblin-infested hills to Mumling’s north.

The Murkwode is a terrifying swampland, cursed, and a rumored den of thieves and pirates.

In a D&D campaign that I’m running, the player characters are exploring the Murkwode and trying to find caves once used by a prosperous thief to horde his wealth and evade authorities.

For those who care, the Mirkwood is a Sir Walter Scott and Tolkien location; the Murkwood is found in the Elder Scrolls. Not to be outdone, I wanted my own version so, murk, as in archaic Scottish, gloomy, and wode, an old English expression for wood, hence, Murkwode.

I’ve written about their prison system as being strict and punishing, yet offering a way out for young men through faith or military service. In true Protestant tradition, punishment is all about spending time to overcoming moral failures, and Mumling’s justice system offers it.

I haven’t written about it yet, but I picture Mumling’s military as small but extremely effective and well-trained.

I see their form of government as a kind of farmer’s grange or a counsel.

I see the people of Mumling as prosperous but humble, isolated, skeptical, superstitious, and religious.

Bartram serves Mumling - not unsurprising given its proximity to the Aevalorn Parishes and their attitudes towards nature.

Aevalorn Parishes

The Aevalorn Wilds are located to the south of the active map. The Wilds is a thick, lush rhododendron forest full of monsters. It is that fear of monsters that has kept the human City States of Gaelwyn at bay.

Halflings look at Aevalorn as the cradle of their civilization; all halflings of The Land trace their lineage to one of the Parishes (consolidated tribes) of the Precursors: the founding mothers and fathers of their various tribes.

Halflings are found in southern Gaelwyn in an area referred to as Aevalorn. To halflings, Aevalorn means quiet home. It is the place of their origin.

Geographic, political, and regional differences between halflings gave rise to Parishes. Aevalorn is home to seven Parishes dominated by a lush rhododendron forest. Aymes Parish lies in the mid-point of Aevalorn.

There are seven Parishes: Valley Parish, Aymes Parish, Greenfield Parish, Tatterfoot Parish, Wetfoot Parish, Applegrove Parish, and Duninish Parish.

There are numerous hamlets that I’ve identified in my work - Pondaroak, Amberglen, Mosshollow, and Ehrendvale.

In The Pig King, I eluded to another human region to the south of the Parishes named Shae Tahrane, an older D&D campaign setting that I created in the mid-2000’s and is currently unmapped.