Blog

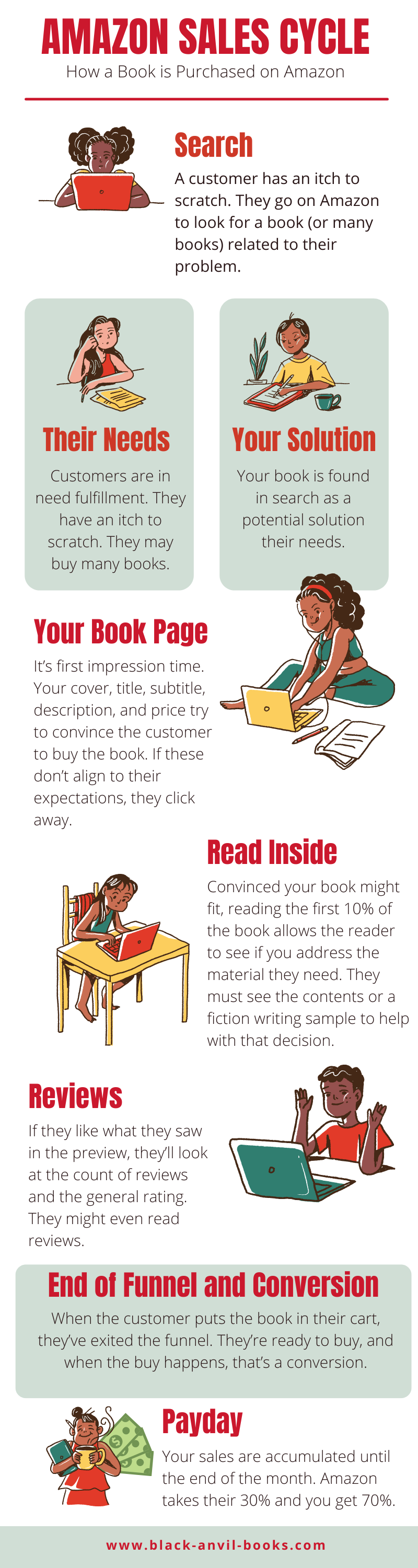

Understanding the Amazon Sales Cycle

Master the Amazon sales cycle: Convert clicks into sales! Learn how to optimize your book's visibility and entice buyers effectively.

If you’ve been following my recent blog posts, I’ve been spending time educating myself on selling books on Amazon. I figured I’d document my process to help other self-publishers like me.

Earlier, I’ve talked about the importance of understanding the long tail. Amazon’s book catalog is 32.8 million entries deep, with thousands of new books uploaded daily to the platform. Visibility is an enormous problem. Knowing your audience is paramount: how will they look for your product? How does your book scratch their itch?

One way to overcome the problem is to ensure your descriptions and keywords match what people are searching for. That’s an organic technique where you research keywords and phrases people will use to find your book; you might even use those keywords in the book's title and subtitle to improve its search relevance.

However, optimizing Amazon and web search is just a small slice of the marketing problem. The challenge we face next concerns converting a potential customer into a buyer, and to understand that, we need to explore the Amazon sales cycle.

Your job is to write a product that scratches an itch: it must meet a need. If you think about how your product meets your niche's needs, the easier it’ll be to prepare search terms and descriptions for your book.

When they land on your book, the cover attracts or repulses the customer. It’s the first element of the buying funnel, and it has to meet their expectations.

Next would be the title, subtitle, price, and description. If these elements fail to convince customers that your book fits their needs in approximately seven seconds, they’ll click away.

Okay, if you convince them to stay, that’s a win. The next step a prudent customer might take is to read the first 10% of the book and examine the reviews. Good reviews are exceedingly important in sealing the deal.

The customer exits the funnel when they add your product to a cart. Now, it’s a buy decision. They’ve selected the work because they consider it worthy and must commit to the buy. That commitment is a conversion.

A conversion is a sale. It’s how you get royalties as a writer. Further, every sale triggers an algorithm in Amazon that addresses the fulfillment of customers' needs, and understanding that referral engine is critical to understanding the sales cycle:

Amazon will now identify you as a preferred author and send emails to customers alerting them to new releases or updates in your catalog.

Amazon will market Pay-Per-Click (PPC) ads similar to your book to the customer.

Amazon will note the demand for your book and — if there are increasing levels of conversions / more sales surrounding your book — your Sales Rank is increased and it starts pushing your book harder to others who share similar interests, putting your book higher in the relevance scores for searches.

That means potentially wider audiences and more sales. Even if your book is being offered for free, it’s still increasing Sales Rank and kicking off the referral engine.

Unfortunately, Amazon doesn’t show us how many people land on our page and engage in our funnels or how long they languish in a cart before conversion, but any of these obstacles may prevent a sale. They’re probably on your page because the Title and Subtitle were sufficient to draw them in. However:

If the cover is bad, they’ll click away.

If the price is too high, they’ll click away.

If the description doesn’t scratch their itch, they’ll click away.

They'll likely click away if they can’t look inside the book, or, if they look inside, they can’t easily find the contents or a writing sample.

If there is an insufficient number of good reviews (and that number may vary for people — I’ve seen estimates of 3+ reviews are just as good as 100+ reviews, and I’m more inclined to believe that as numbers become nebulous to ordinary people beyond 10) — they’ll click away.

Studying user activities with these elements, doing your market research, and getting feedback from your reader and writing communities is fundamental to walking the customer down the funnel to conversion.

How to Manually Select Amazon Keywords

Here are some quick and dirty instructions for selecting quality, high-demand keywords for your book on Amazon.

I’ve spoken about the long tail when marketing your Amazon book. I talked about the importance of discovering your niche, mapping out your keywords, and building keywords into your title and subtitle.

Here’s how you can manually select useful Amazon keywords for your book.

Use Incognito Mode on your browser. This is so previous information doesn't affect what Amazon shows you.

Select “Kindle Store” or “Books” as the Amazon category to focus on the area of Amazon you’re interested in.

Start by typing in a word. Amazon immediately pre-populates in the search box. Think like a reader. Imagine how you’d search if you were a customer.

Once you've found a phrase that interests you, add each letter of the alphabet at the end of your word/phrase, and see what comes up. “High fantasy a”…, “High fantasy b”…, “High fantasy c”…

Make a list of phrases a reader will most likely look up. Mix and match the phrases in different combinations.

Amazon is showing you what it thinks to be the highest-ranking term in descending order, so it’s already showing you the demand for the full keyword.

Choose up to seven keywords or phrases, up to 2500 characters per keyword or phrase.

These will be the keywords you’d use to set up the ebook.

You can refine the keywords later by editing the book.

In fact, editing an ebook re-indexes the book, making it more relevant to A9 (Amazon’s search algorithm). The more up-to-date a book and its metadata is, the better.

R

Using Keywords in the Title and Subtitle of an Amazon Book

How to use SEO organically in your Amazon book’s title and subtitle.

Amazon uses keywords and phrases in at least five specific places concerning books and ebooks.

The Title.

The Subtitle.

The Product Keywords at Setup.

The Product Description.

The “Look Inside”/Read Sample.

Let’s talk about two of these areas for now: the book’s title and subtitle.

The Book’s Title

It’s probably the most valuable piece of keyword real estate because Amazon wants to match against a book title directly, but it’s probably the hardest area to work in a keyword or phrase. If you could take a keyword and make it a book title, you’re optimizing for SEO in the greatest possible way, but it’s unrealistic. Few people will buy a fiction book titled “Fantasy Short Stories.”

The Book’s Subtitle

But a subtitle is nearly as good. Take a look at this example, Legends & Lattes by Travis Baldtree. When I grow up, I want to be like Travis.

It is no accident that the keyword “Novel” and phrase “High Fantasy” appears in this piece. Look at the keyword analysis.

Competition is high on the phrase “high fantasy novel” but low to medium to “novel” and “high fantasy.” It’s placed in the subtitle so it creates a good match. Let’s consult Amazon.

And look, there it is! The 5th suggestion down the list.

My Amazon Keyword Tool concurrs.

The gold score under Est. Amazon Searches/Mo indicates that the search volume is reasonable at an acceptable level of competitiveness.

This is A9 (Amazon’s algo) telling us that the phrase “high fantasy novels” is commonly searched, so, it’s got a lot of demand and is probably more expensive from a PPC point of view, but Travis here has it organically baked-in to his subtitle!

When I run the search, Legends & Lattes is the 5th book in the list. He’s at the head of the tail and doesn’t have to pay a dime for placement.

Building on SEO Principles in the Subtitle

Many factors will influence my list results, including the cookies in my browser and the history of my own searches on my account, but, even in an incognito window, I get the same result.

If you’re wondering, that’s not by some happy accident. The SEO is organic, but it’s planned.

When planning your subtitle, think about keywords, yes, but also brainstorm keywords for pain points, desired results, emotional amplifiers, and demographics.

Think about this:

How to Murder Your Husband

Not a bad title. People look for that phrase ~10,000 times a month, and it’s got low competition; few people are paying for that real estate.

But now sprinkle in a little SEO goodness.

How to Murder Your Husband:

A Woman’s Guide to Success

Yeah. You see it, right? I’m targeting married women (a demographic) who want to exit a troublesome marriage successfully. But maybe a little more:

How to Murder Your Husband:

A Smart Woman’s Guide to Financial Success

Divorce is financially painful and messy. Wouldn’t murder for a smart woman like yourself just be easier? Being poor is a pain point. And don’t you want to exit the marriage successfully? That’s ambitious! And the whole construction is rather emotionally amplifying, wouldn’t you say?

Happy April Fools.

Still, thinking about SEO when constructing your title and subtitle is an organic way of manipulating search engines to bring your titles to the head of the long tail, improve reader visibility, and, hopefully, increase unit sales.

R

Selecting the Right Keywords in Amazon as a Self-Published Author

Authors must perform keyword research to unlock their potential with the right keywords. Keywords are the secret to being seen on Amazon and Google.

Hey there, aspiring author!

Have you ever wondered why your brilliantly crafted articles or books aren't getting the attention they deserve?

The secret might lie in something seemingly mundane yet incredibly powerful: keywords. Let's explore keywords and why choosing the right ones is important for being seen in the long tail.

What Are Keywords?

Imagine the Internet as a giant library, and search engines like Amazon, Google, or Bing are the librarians.

When someone looks for information, they type in keywords to find the most relevant books or ideas. They're the signposts that guide search engines to your digital doorstep.

Keywords are directly related to your chosen niche—the audience you’re trying to reach who might be interested in your writing.

Drilling Into the Long Tail

Keywords are often more than just one word (they’re more often a phrase) and can be broad or narrow. A broad keyword would look like an overall reaching subject:

Travel Books

Fantasy Novels

Military Science Fiction

These broad, highly competitive terms are generally meaningless as a tool for finding your book. It’s like browsing Fantasy Books in a bookshop, except that section is 40 city blocks alone. Your book’s in there somewhere, but nobody will find it.

Instead, relevant keywords drill into the long tail. They get more specific.

Dark Fantasy Novels

Dark Fantasy Short Stories

Novels Featuring Female Protagonists

Notice the influence of understanding your niche here. Your readers use special terms and vocabulary related to their interests to help drill into the long tail.

For me, much of my fantasy writing is connected to role-playing games. Fantasy readers and Gamers of all stripes are my niche, so I might drill deeper into my niche using their vocabulary.

Dark Fantasy Novels Cleric

Fantasy Novels Paladin

Books About Red Dragons

These are more relevant keywords that draw my audience to my work. They’re less in demand as a keyword, and fewer people search off of them, but they’re also less competitive. Fewer people are willing to bid (pay money) on those terms.

Make a List of Relevant Keywords

Start by considering keywords and phrases most relevant to your writing and work. For me, my keywords might look something like:

fantasy short story

dark fantasy short story

fantasy series

strong female lead fantasy

dark fantasy book series

free short stories fantasy collections

fantasy books about witches

fantasy witch books

When brainstorming keywords, think like a book consumer. How will people find you in the long tail? What will they be searching for? The more granular the phrase, the deeper it gets into the long tail.

Not all keywords are created equal. Some keywords are worth more than others. In the world of SEO (Search Engine Optimization), you must understand two metrics about words: the demand (frequency) of the phrase and its competitive rank.

The demand for a keyword represents the frequency of use; how often it gets typed into Amazon.

The competition for a keyword represents what people will pay for that valuable real estate. Competition reflects how many people want to be featured first in the search results for a high-demand keyword.

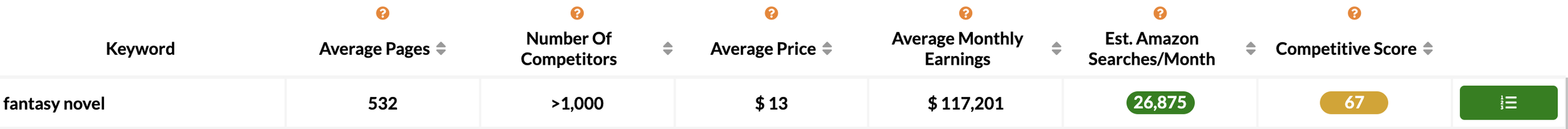

For example, if you take the keyword “fantasy novel,” you’d find it has high demand and competition. It’s frequently entered into Amazon.

The price for that keyword is very high (this concept is related to Pay-Per-Click advertising, but conceptually, look at the problem as real estate — everyone wants that space, and there are people with big budgets willing to pay for the position.

But how do I know if a keyword/phrase works? How many searches per month are there for “fantasy witch books” anyway?

Using Keyword Analyzers

How do I know this? I must use a keyword analyzer. Here’s “fantasy novel” using Google’s Keyword Analyzer.

Look at the Average Monthly Searches (Demand). Although competition is high for both, there’s fewer searches for the “dark fantasy short stories” than “fantasy novel", and the bid price for the “fantasy novel” is notably higher. This is the effect where “dark fantasy short stories” is more niched. It’s going deeper in the long tail.

If there’s a lot of competition, you’re likely to be drowned out in the noise of other search engine results or from parties willing to pay to be in front of you. Because of that, you have to get closer to your niche. Just look at an Amazon Keyword Tool’s result on “fantasy novel”. This is Publisher Rocket, by the way. Dave Chesson has a great novice-level program for SEO work on Amazon.

Almost 28,000 people search for that phrase on Amazon in a given month, it returns 500+ pages of books, and it’s highly competitive, scoring 67/100 on a competitive score. Yikes.

From a PPC point of view, I’m paying less for “dark fantasy short stories” than “fantasy novels” because there are fewer monthly searches; it’s less expensive real estate. But it digs deeper into the long tail and speaks to my niche, the audience I’m after.

Finding the Sweet Spot

But here’s the catch: if you use generic or incredibly obscure keywords, you'll be in a queue behind thousands of others or in a dark, dusty corner where no one thinks to look.

The art, then, is in finding that sweet spot—keywords that are specific enough to stand out but common enough that people search for them. Something with medium demand. Ah, take a look at this.

So here we go. Closer to my niche (short stories rather than novels), more demand (100-1k searches/mo) at negligible costs. This is basic keyword research, telling me:

“Fantasy Novels” are at the head of the tail. It’s the most searched term and the most expensive piece of real estate to rent. The competition drowns me out, and my PPC budget will quickly be eroded.

“Dark Fantasy Short Stories” is more obscure and maybe more attractive in terms of cost, but there is little demand. Few people search for this phrase on Google in a given month. My PPC budget is more cost-effective, but I will wait a while for people to come around.

“Fantasy Short Stories,” however, is the sweet spot. It gets more traffic, so there is medium demand, but the cost is negligible (tiny in this case). My PPC budget is more cost-effective, whereas my website or book is being seen in search results more often at a lower cost.

Therefore, according to Google, “Fantasy Short Stories” should be one of my keywords!

Well, maybe.

This is an Amazon Keyword Tool result.

Now, my Amazon tool isn’t so sure.

On Amazon, less than 100 people type it into their search engine, and the value of a 7/100 as a competitive score suggests few are trying to hone in on it. Still, that’s good for me! No competition!

But let’s go back to one of my previous ideas, Dark Fantasy Stories.

Okay, look at that! A relatively low 23/100 competitive score with a reasonable level of searches per month - 950 people typed that into Amazon in one month. To recap:

Fantasy Short Stories - Good with Google Search.

Dark Fantasy Stories - Good with Amazon.

So where should I use them?

In product descriptions and keywords in the Amazon listing? Yes. Maybe I’ll try “Fantasy Short Stories” for a while before replacing it with something else.

On my website? Yes.

As meta descriptions for books? Like, in the subtitle of a book? Yes.

On blog posts like … er, this one? Yes.

Tools like Google's Keyword Planner, third-party Amazon A9 keyword tools, or other SEO (Search Engine Optimization) tools can help you find similar terms people are searching for, their popularity, and their competitiveness. Sometimes you have to pay for these things.

You should be prepared to pay for information that makes you more competitive, but good news: Google Keywords can be used for free.

R

Finding Your Niche as a Self-Published Author

Find your niche audience and cultivate a community of engaged readers. It's about quality, not quantity.

Self-published authors face a daunting challenge: not only must they create unique and compelling content, but they must find a market for it that exists somewhere in the long tail.

Niches

It’s incumbent upon you as a self-published writer to find your niche. Knowing who you’re writing for can transform your writing journey to make it both rewarding and successful.

Firstly, understanding yourself is crucial. Who are you? What do you want to write about? What are your interests? How do your interests influence your writing?

Sun Tzu, guys: If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles.

If you don’t understand why you’re writing and what you’ll consistently write about, stop. Go back and stare in a mirror until you figure it out.

Second, find your niche. These people share your interests and want to read your writing. Understanding your niche is crucial. This involves recognizing who your ideal readers are, what they crave, and where they spend their time online. What do they want from a story?

Whether you're penning sci-fi novels, self-help books, or historical fiction, there's a community for you. The key is to engage with these communities authentically.

Social media platforms like X, Instagram, and Goodreads offer fertile ground for connecting with niche readers.

On X, hashtags related to your genre can lead you to conversations with potential readers. Instagram allows for a more visual connection, showcasing your writing process, book covers, and themes through engaging posts.

To effectively use these platforms, be consistent and genuine in your interactions. Share your journey (writer-slang for how you go about writing), ask questions, and participate in discussions.

It's not just about promoting your book but building relationships with your readers.

Third, engage. You can be a lurker; you have to participate in these communities.

Over time, you'll find your niche audience and cultivate a community of readers who are genuinely interested in your work.

Strategy:

Figure out who you are and what you’re writing about.

Find your people.

Engage with them.

Remember, connecting with your niche is about quality, not quantity. A dedicated group of engaged readers can be more valuable than a vast but indifferent audience.

R

Navigating the Longtail in Internet Marketing

Self-publishers must embrace the long tail to find their niche and connect with dedicated readers.

If you are marketing your self-published book, understanding the long tail concept is like discovering how gears in a clock track time.

Imagine walking through a market that stretches beyond the horizon, where every stall offers something unique. The first stalls you see are the largest and loudest, manned by the most popular authors. Your stall, on the other hand, is way out in the distance, further than you can see, where you eagerly await a customer to come walking by. Will they ever?

This is the digital marketplace, and the long tail is its most intriguing secret. The more you understand the long tail, the greater your appreciation for SEO (Search Engine Optimization) will become.

What is the Long Tail?

Originally a term from the business world, the long tail in self-publishing refers to the plethora of niche genres and topics that, when combined, can equal or surpass the market share of bestsellers. This means authors no longer need to chase mainstream success to find their audience; there's a space for every unique voice.

Amazon maintains a catalog of 32.8 million titles. That’s a lot of books! What is seen and what sells represents an absolutely tiny fraction of their total catalog. What sells is at the head of the curve; what languishes in obscurity is in the tail of the curve.

As a new or self-published author, your book lives in the tail of the curve.

Why it Matters

The long tail strategy empowers authors by highlighting the importance of niche markets. Those catering to specific interests can stand out in a sea of millions of books. This approach benefits both authors, who can write about what they truly love, and readers, who can find books that resonate on a personal level.

Your job is to move your products up to the head of the curve through SEO, marketing, likes, recommendations, shares, good product reviews, and promotions.

Sounds expensive. It is. So how do you do this?

Leveraging the Long Tail

The long tail strategy for self-publishing authors involves identifying and targeting readers in specific niches. You must find an audience that traditional publishers have difficulty reaching.

The right niche aligns with your interests and expertise while having strong market demand. This builds authority and attracts your ideal readers from knowing your audience.

That might mean writing for a narrowly defined genre.

Authors can connect with their ideal readership by utilizing targeted marketing strategies like SEO and social media engagement.

Embracing the long tail in self-publishing opens up a world of possibilities for authors and enriches the literary landscape with diverse voices and stories. It's a testament to the power of the internet to connect writers with readers, no matter how specialized their interests may be.

The Internet makes this process easier than ever.

R

Cats and Oranges

On Oranges

Years ago, my wife and I attended a theater show where oranges were rolled onto a stage during a live performance. The actors, still thoroughly engaged in the story — dancing, moving, repeating their lines — struggled to avoid slipping on the oranges. Some, in fact, did, and when it happened, I burst out in laughter. I couldn’t help myself.

Well, my outburst wasn’t well received. Most of the audience turned to glare at me as if I was some Neanderthal who didn’t appreciate good art.

I use this story to illustrate the problem of art. A rolling orange can be one person’s serious artistic statement and another’s comedic moment. Art is entirely subjective, and what constitutes artistic expression isn’t up to us, but the judgment of our audience.

In the art of writing, we use the tools of our craft to relay a story to a reader.

We have nouns and verbs, adjectives and adverbs; we have intensifiers and modifiers. We have punctuation, sentence structure, and paragraph sequences. We have tools like flashbacks and flash-forwards. We have perspectives like 1st and 3rd person. We might tell more than show. We might have a story of one word, a hundred words, or a hundred thousand words. We strive for eloquence and brevity in our expression and, for some, capture universal themes of the human experience in our writing.

Oranges are our art. How well tell a story is the subjective choice we make as authors to relay how we feel it should be told. When someone judges our writing and experiences our art, they see it through a lens of their own personal experiences and biases. They might not like nor prefer the tools we used to tell it and may score us poorly. If anything, poor use of oranges may diminish our credibility in the eyes of readers, judges, and publishers.

On Cats

Cats, on the other hand. Everybody likes cats. People are obsessed with cats. People share cat pictures all day long. People love cats.

Cats are the bread and circus of writing — they’re stories readers want to read. A cat is what a reader expects when they read your story. Whether or not it’s a horror, romance, or adventure, readers have certain expectations about what that story should feel like. The major scenes. The characters. The action.

I often use the phrase “writing a good cat.” People must be attracted to the story to read it. They must want to pet and cuddle with the story, scratch behind its ears, feel good with it, and ultimately share it with others.

As a writer, my ability to “write a good cat” relates to telling a good story, regardless of the oranges I might have used to tell it.

On Writing Contests

In traditional publishing, we want to write stories with a good balance of oranges and cats.

Our oranges establish credibility with readers and publishers, and our cats compel our publishers to keep buying our stories, and readers to keep reading our stories.

Writing contests, however, are different.

Some contests are more cats than oranges; some are more oranges than cats.

In my opinion, peer-based contests like Writing Battle require a cat-heavy story to be successful. Stories must meet genre and connect with a broad audience of amateur writers. They don’t put as much weight in the oranges we use to tell the story; readers want a good cat. If you fail to tell a good cat, regardless of how beautiful your oranges, it will fail.

On the other hand, prestigious amateur contests like NYC Midnight and GlobeSoup require more orange-heavy stories to be successful. These are contests judged by more seasoned, if not professional, writers, not amateurs. The stories that win these contests must pass a litmus test on how those judges perceive the art. It doesn’t matter how astounding your cat is. You might write a very compelling and attractive story, but if the oranges don’t line up with the expectations of the judges, you will fail.

How You Can Tell

In my opinion, you can tell what a contest is like by reading their past winners.

Orange-heavy contests will showcase slow, dull, prodding stories on typical themes that are expertly told. No risks are taken, and there’s no excitement in the story — it’s all very bland and predictable — we’re bored, as readers, because we’ve read these stories before. But that’s what the judges expected, so it’s what the writer wrote.

On the other hand, stories (art) that are more exciting, out of the box, and fun to read, enjoyed by many regardless of technique, that take risks on art, are more cat-heavy. They’re the surprise hit experts didn’t expect, or, when we read them, may completely disregard traditional oranges. They’re stories that resonate with people, regardless of the tools and techniques used to tell them.

On Cats and Oranges

If we’re writing for contests, we generally have to write a good cat stuffed with oranges, or, as the picture above suggests, a good orangey cat. The story itself has to be compelling and meet the reader’s expectations, and our use of the art must not distract from the story or penalize it.

Now, in my opinion, some writers might gravitate towards one or the other.

Authors might struggle to win peer-based competitions but may excel in writing a predictable story well. They’ll shun the erratic, unpredictable nature of these contests and declare them “not real writing contests.” They’ll upturn their nose and go to where they’re appreciated.

On the other hand, the creative writer who fails in a structured, oranges-heavy contest may be so frustrated by the judges’ gatekeeping that they vow never to pay the $30 entry fee again and go home. They might even pack it in as a writer and give up.

The trick, I think, is found in adapting to the expectations of the contest and being mindful of both problems. At the end of the day, I think most writers would agree that cats and oranges make for better writing. We have to write strong, relatable stories, that people want to hold in their laps, and to do that, we often have to take risks and use our tools in ways that are exciting. Unpredictable. Even if they don’t meet the formal expectations of a literary judge.

Why I Write Short Stories and Novellas

Generally, I write short stories (<5000 words) and novellas (10,000 - 40,000) words.

Why? A couple of reasons.

First, rewriting a novel is a disheartening slog, and I use the term ‘rewriting’ intentionally: it’s a project that never ends. It’s a toil. For some, it can consume upwards of two years, and really, novels can languish for decades and never get done.

The prospect of endlessly working on just one endless project ticks me off. I’d much rather work on something with a definitive start and a definitive end, and even if I reworked it, it’d take a month, not a year. That just makes me feel happier.

Second, people wrote novels because it was the form expected by traditional publishers. As I recently wrote, modern books are electronically published, reproduced, and distributed at zero incremental cost. It doesn’t matter if my work is 300 words or 30,000 words: I can distribute both exactly the same way for free.

So who cares?

Finally, I think there’s a transition happening with consumer preferences and books. The very act of reading is changing. Few people are reading, and when they do read, they’re reading in shorter bursts of time. They’re reading on mobile electronic devices with smaller screens, like tablets and phones, where they can control the flow, typesetting, and introduction of new content. Bursts of reading activity with smaller samples, like, 2,000 words, benefit the serialization of fiction, where consumers are digesting reading as they would a series from Netflix. They’ll read one 2,000-word episode and return to the new episode later, or if they’ve time, binge 2-4 episodes at a time, not paying for an entire premium price of a novel, but instead paying for what they use/consume. I feel I’m writing in a format desired by modern consumers, perhaps at the exclusion of older consumers who prefer to own (rather than lease) thick, chunky novels at premium prices.

Generally, I write around 5,000 words a week so I can usually get through at least one book project a month. You know, there’s something comforting about starting a project and finishing it. Isn’t that what all writers really want? To play with an idea, build it out, and then move on to the next great thing?

Again, that idea just makes me happy. And if you write and bury yourself for two or more years in a writing project that just erodes your soul, I just don’t understand: why would you do that?

You don’t need to. Not anymore.

R

What is a Book?

As an author, technology professional, and digital native, I think it’s beyond time to ask ourselves what a book is, and how technology has broadly transformed the business of publishing.

What we traditionally identify as a book is a certain dimension and size; something that was physical and has pages that we manually flip through to read in consecutive, sequential order; that it has a spine; it has a cover and a jacket, requiring layout designers, typographers, and visual artists.

Because books were physical, there needed to be a process to edit it and make sure it was right. Errors and omissions couldn’t be corrected in the finished product.

In order to make a profit off the product of a book, it had to be economical to produce it. There had to be at least x-number of pages printed under certain constraints to make y-amount of profit. Historically, the profit motive is what filtered writers from being published at all. Publishers knew that, in order to make a profit off a book, there was a formula associated with the cost of production, requiring a minimum and a maximum number of physical pages, in specific dimensions and materials (paperback vs hardcover, for instance).

In order to sell the book, marketers knew that there was a formula that worked: a strong character-driven story with a three-act structure with lots of escalating, high-stakes action, in regards to a fantasy novel, for instance. They knew that a man had to write it; the fantasy demographic repelled female authors. They knew that the protagonist must be a human male to best identify with the reader, and in particular, a white human male. They knew it needed a splashy cover and vivid colors, and it needed to be between x-number of pages, otherwise, a segment of the market wouldn’t be interested in it.

Publishers knew how many units they needed to produce and sell in order to make a profit off the volume. Thus, they made exclusive arrangements for marketing and distributing a book. These exclusive arrangements allowed for a certain amount of time a book sat on shelves, and was calculated from the amount of loss they’d suffer if they didn’t churn the inventory quickly enough. In most cases in the latter half of the 20th century, publishers had to buy-back underperforming books from the retailer and eat their losses.

Authors of traditional books were disconnected from their readers because they had no way to speak to them at scale without the marketing muscle of the publisher.

And physical books suffered a long-tail problem: they’d need to be taken into the storeroom within eight weeks or so to make more room on physical shelves for more product, physically leaving the consumer’s sight and imagination. Only books at the forefront of the consumer’s attention and imagination are what sold; anything else in a store room or warehouse was inaccessible by the consumer.

Therefore, up to the year 2010, there was a lot of gatekeeping that went on in the publishing industry. Fantasy books were costly to produce, expensive to distribute, must meet a slew of criteria to be successful, and excluded female authors and protagonists that didn’t mirror their readers. Authors couldn’t cultivate their own marketing relationship with consumers, and books had an eight-week lifecycle at most.

Throughout the 20th century, those filters, the sheer risk of publishing a book, generated mountains - continents - of rejection letters because, if we’re to be honest, who’d want to be a publisher anyway? Tons of costs, lots of risk, and tiny profits. Publishing sucked as a business model, and retail wasn’t any better. Only scale made money; i.e., Barnes & Noble killing traditional booksellers - remember that?

So what happened in 2010?

Around 2010, a number of factors converged to destroy traditional publishing.

The Internet had created a generation of consumers prepared to consume electronic content;

Broadband - fast, inexpensive Internet access had been brought to most of the industrialized world, and used routinely by lower-middle-class consumers;

The arrival of viable tablet-based computing platforms, allowing one to reasonably hold an electronic copy of a book in facsimile to a traditional book;

Electronic distribution platforms for booksellers allowed retailers to produce print-on-demand products, build electronic products on their platform, and resell and distribute digital media at scale;

Social media allowed authors to disintermediate the publisher and talk directly to consumers, to build their brand as an individual;

The proliferation of secure, nearly costless, Internet-based payment systems enabling an author to sell directly to consumers.

These influences are ongoing and erode the power and profitability of traditional publishing. Very soon, the traditional publishing world will be reduced to just a few players for, in a world where you make < 5% on printed products, scale is everything. M&A like Penguin Random House and Simon & Schuster must happen, otherwise, there is no scale, only efficient competitors, eroding each other’s market share and driving prices to the bottom; nobody will make money, and there will not be any more traditional book publishing business. It simply costs too much and there’s no money in it. If consumers don’t mind paying a premium for a book ($30/unit vs, say, $10/unit electronically), then not a problem. I’d be willing to bet, though, that sentiment will not last, no matter how people like the physical feel of a book in their hands.

So, what is a book?

Today, it a book is digital media - it’s an electronic product.

A book can be created by anyone with a computer.

Books are software. They can be edited and changed at any time, providing instant updates, and released through versioning - just like software.

Authors can grab an ISBN directly electronically; they can manage their own catalogs and meet reseller requirements for inventory and distribution; they can print-on-demand, doing one-off unit-based printing at practically zero cost to them, eroding maybe 2% of their margin.

An electronic book can be distributed at zero cost to anyone, anywhere, in the world, and run off any digital device. There is world-wide distribution of a book at zero cost with no licensing intermediary eroding your margin.

It doesn’t matter what size a book is - how many pages or words; in this case, size doesn’t matter. The costs of production and distribution are exactly the same. A book can be replicated a zillion times at no cost.

The longtail is overcome by filters, social media, and search. Consumers can dig into catalogs with millions of titles and find what interests them, and social media can help market titles to new readers.

A book can be marketed directly to consumers by authors, allowing them to make their own brands and relationships. No longer does a publisher get to intermediate that relationship, allowing anyone, anywhere, to create a following of readers.

Its typesetting doesn’t matter. The consumer, not the publisher, can choose their own preferences for typeface on their digital readers.

In an electronic format, books are extensions of digital assistants like dictionaries, thesauruses, note taking and research/citation tools, and Internet search. A single in-narrative click can help inform a reader or lead them to more engagement with the author online.

Editing and art assets are increasingly cheap - most of that labor can be outsourced using Internet based freelancing - allow authors to access quality talent at increasingly lower costs. And one day, AI-generated imaging will offer authors free high-resolution artwork at zero cost.

The development and publishing of a book is highly automated. If you can learn how to press a couple of buttons, you can move data between - what used to be - complicated formatting changes.

In essence, the author is their own publisher, editor, and marketer, and they have direct access to the market and consumers from which to create and maintain their brand. This is simply the dream of authors like Richard Brautigan - we are all publishers.

I am fortunate enough to live in an amazing time of transformation in this industry. The nature of what a book is has radically been transformed.

I generally write short stories (~10,000 words) and distribute them world-wide at no cost, about characters and settings that’d usually be gateway’d out by traditional publishers. But with today’s model, I can write and distribute anything of any size. Who’d want to read novellas about Halflings anyway? Well, I’m lucky enough to just do my own thing and improve my art to connect with audiences and build my own brand. What an amazing time!

The era of waiting around for someone to validate you as an author with an acceptance letter is over. You are an author; you are a publisher. Even traditional publishers vet authors based on their skillsets in developing their own work - they’re more likely to hire someone who comes in with an audience of 10,000 readers and an established catalog of content, than someone who doesn’t already have it. Why put a risky bet on someone who can’t do it themselves?

Even as I write this, though, I’m very much aware that another transformation is in play concerning AI (Artificial Intelligence). In the very near future, most of what readers consume will be written by automation - computers trained on writing specific forms of content, creating amazing works of art that will compete with even the best of us human authors. So the ability to be seen, hired, read, and compensated as an author will continue to meet headlong forces. I write because I like telling stories; not because I think I’ll make any money at it, and that concept of making money is probably unrealistic.

In a world where computers produce written content, only a miniscule percent of authors will actually make money in this business. True talents will own their own brand, disintermediate publishers and booksellers, and go directly to their audience, who will circulate their work in social media as to attract new readership; all the while, they’ll be under constant threat from AI that can emulate their unique style at a drop of a hat.

What is a book? And what is an author? Well, both are rapidly changing.

Take advantage of change. You, as an author, no longer need to wait around for someone to tell you you’re good enough. That’s crap - go publish now! And publish every day.

Thanks for reading my work.

R

Why I Write Stories About Halflings

Like most everyone, I was first exposed to Hobbits reading Tolkien’s work.

The Lord of the Rings movies produced by Wingnut Films didn’t come out until I was in my thirties, so my earliest impressions were from actually reading the books, and, the Rankin Bass‘ productions of The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings.

When I started playing role-playing games in my teens, D&D helped to inform more about halflings, particularly images drawn by Jeff Dee.

At the root of it, what I love about halflings is their appreciation of hearth and home. Tolkien’s adaptation of the word to develop an 18th century culture of charming portly naturalists - who value connection, family, friends, and food ahead of monetary gain - gives us (as readers and authors) an opportunity to reconnect with those values.

At the same time, I like writing about Halflings that do the unexpected. I like writing about characters who went beyond the stereotype and expand on Tolkien’s concepts.

Jeff Dee’s images of svelte, muscular halfling adventurers took those original Tolkien concepts portrayed (lovingly and accurately) by Rankin Bass into something different. It took the original pallet and expanded on it, and I really loved that idea.

As a gamer, I often played halflings because they had that interesting dichotomy of wholesomeness and home blended with luck, curiosity, a bent for exploring, and an intense desire to go back home; Weis and Hickman’s Kender in their Dragonlance saga only pushed that envelope farther. I loved playing those kinds of characters and expanding on what Tolkien originally gave us.

In writing about halflings, I enjoy the fact that they’re a literary shortcut that builds off of all of these other ideas about them. It’s shorthand: a way of describing something the reader already knows, and it allows me to cut back on writing lengthy descriptions of characters, scenes, or motivations. Shortcuts are really necessary in writing serialized fiction because you don’t have the time to elaborate on details.

Finally, I like writing about halflings because they’re often depicted as sidekicks to protagonists. They’re more likely to facilitate an outcome, or be comedy relief, than a central hero. I think that’s what really motivates me to write about them because, like Bilbo and Frodo, halflings do represent the hero. They portray the idealistic who doesn’t want to fight but must to protect heart and home, or, the undaunted, child-like exploration of the world.

Either way, halflings offer a quick way to jump into these ideas in Aevalorn Tales.

R

How Things Started

Elements of Trelalee, Gaelwyn, and Aevalorn started as D&D campaign settings from 2014. Having finally reached a point in my life where I felt I had the time to write serialized fiction, I really wanted to go back and explore this world a little more.

Hi - thanks for stopping by, and thanks for reading my work.

I started playing Dungeons & Dragons (D&D) in 1980. I was ten. I had already started reading sci fi and fantasy; at the time, I don’t think there was a young adult fantasy genre, rather just serious fantasy (Tolkien, Brooks, Eddings, McCaffrey, Moorcock) and what I’d call light fantasy (Weis and Hickman, Salvatore, Pratchett, and numerous “Choose Your Own Adventure” books). I adored both.

But as a kid, I really found myself pulled towards the latter because those stories had a hook into role-playing. I guess I could relate to it. I enjoyed picking out gameplay elements of D&D from I was reading - no doubt due to TSR’s brilliant marketing - and I so I kept buying new books. Back then, spare cash and I were often parted due to my D&D habit.

The White Stands, the Free City of Trelalee, Fenwater Abbey, Gaelwyn, and Aevalorn were concepts created for a D&D 5E campaign I developed in 2013. Having finally reached a place in my life where I could devote time to write, I decided to explore these ideas again under a serialized fiction platform, Amazon’s Kindle Vella.

So maybe a part of this is to reconnect with my childhood. It’s something like that for me, yes, but it’s also a “do or die” thing. If I don’t start writing now, I’ll likely die before I get an opportunity. Now is better than later.

It also turns out that I’ve created a ton of stories for role-playing games over the last 40 years. I’ve so many worlds, characters, and ideas sitting idle in old notebooks and electronic files that it’d be a shame not to leverage them. Sure, world-building and story-writing for role playing are apt skillsets for novelists and writers, but I’ve also a technical background that lends to modern self-publishing. Further, I’ve enough idle time to write. Therefore, I guess it’s just a confluence of happy coincidences.

Today, when I write about Trelalee and Gaelwyn, I feel that same connection that I’d felt as a kid between playing RPG’s and reading fantasy novels based on those settings. It’s still a real kick for me. I can’t say that I spend a lot of time rule-mongering and checking my writing against game mechanics, but I will admit that the 5th Edition rulebooks are nearby when I draft my outlines. I’ll also say that those older, more dusty books written by serious fantasy authors are nearby, too; they’ve always been a part of me.

Thanks for coming along for the ride.