Blog

The Gallant Gerund

Unlock the gallant power of gerunds! Learn how these action-packed nouns bring dynamic energy and fluidity to your writing, making your sentences truly shine.

So there I was, writing a blog post about verbs, when I went to discuss gerunds, transforming my 500-word blog post into a 2,000-word monster. Therefore, I’ve broken out the topic into its own post for your pleasure.

I believe it’s warranted. Gerunds are great, but new writers tend to abuse them, so let’s explore what they are all about.

Gerunds

I love gerunds. Maybe … too much. I have to take special care not to overuse them.

A gerund is a verb that ends in -ing and functions as a noun in a sentence.

Instead of showing action like a typical verb, a gerund acts more like a thing or an activity.

For example:

Running is my favorite hobby.

Writing helps me express my thoughts.

In these sentences, "running" and "writing" are gerunds because they are being used as the subjects of the sentences (activities) rather than showing action.

Gerunds can also function as objects:

She loves cooking.

He avoided talking to the stranger.

Even though these words look like verbs, they're playing the role of a noun, showing what the subject loves or avoids.

Abusing the Gerund

Gerunds can be "abused" when overused or used awkwardly in a sentence, leading to clunky or unclear writing. Here are a few ways this can happen:

1. Gerund Overload

When multiple gerunds are used in a single sentence, it can become hard to follow or sound unnatural.

Example of overload:

Running, swimming, and hiking are what I enjoy doing after working.

A cleaner version:

I enjoy running, swimming, and hiking after work.

The sentence feels smoother when there aren't too many gerunds competing for attention.

2. Unclear Subject or Ambiguity

Sometimes, overusing gerunds can cause confusion about who or what is performing the action.

Example of ambiguity:

Walking the dog while eating dinner can be tricky.

Is walking or eating tricky? And who is walking the dog — someone or the dog itself? To avoid confusion, it's better to clarify:

It's tricky to walk the dog and eat dinner at the same time.

3. Awkward Sentence Structure

Relying too much on gerunds can lead to awkward sentence constructions that sound stilted.

Example of awkwardness:

The playing of video games all day is frowned upon.

A smoother alternative:

Playing video games all day is frowned upon.

The Gallant Gerund

Gerunds are exceptional — even gallant — because they possess a unique versatility.

They Can Be Dynamic Nouns: Gerunds have the elegance of transforming actions into entities. They let you describe an activity like running or swimming as if it’s a tangible thing, adding depth and movement to a sentence. Instead of just doing something, the action itself becomes the focus, like "Running is my passion." This flexibility makes gerunds stand out among nouns.

They Offer Effortless Flow: Gerunds can smoothly link ideas in a natural and fluid way. Their ability to maintain the energy of a verb while acting as a noun gives sentences a graceful rhythm, allowing your thoughts to flow without awkwardness. For instance, "He enjoys cooking and painting" carries an effortless blend of activities without feeling forced or heavy.

Gerunds bring both dynamism and balance, making them a gallant tool for creating expressive and fluid writing!

But as for abuse, if you find that gerunds are weighing down your sentences, try rephrasing them or using more straightforward verb structures to keep the flow natural.

And here's some advice:

If you’re submitting your work to a publishing editor or contest judge, take your story to ChatGPT (or an AI of your choice — I’m commercially agnostic around here) and have it identify all of the gerunds, scene by scene. The results might surprise you. They may be an unconscious crutch in your writing. It’s something an experienced judge or editor will catch.

R

Finding the Right Vibe with Verbs

Discover the power of verbs and how they drive your stories forward. Master the action, avoid passive voice, and take your writing to the next level!

Verbs … move.

They’re the vibe you’re looking for.

Verbs are the action heroes of the writing world, giving your sentences life, energy, and motion.

Without them, well, your story’s going nowhere! And I mean literally.

Jimmy ___ by the fountain to ___ the water ___ across the surface.

Blech. What exactly is Jimmy doing with the fountain? What’s happening here? Where’s this turkey author taking me anyway?

Verbs move the story.

So, today, we're diving deep into the world of verbs. Whether you’re a newbie or just brushing up on your skills, this is your ultimate guide to mastering those action-packed words.

What Exactly Is a Verb?

In the simplest terms, verbs are words that show action or state of being. If your character is running, jumping, laughing, thinking, or even existing, verbs make it happen.

Verbs are the engine that drives your story forward.

Almost every sentence requires a verb.

Without verbs, you'd have a bunch of nouns just sitting there, like “Jimmy,” “the fountain,” and “the water.” And while that might make for an interesting art exhibit, it’s not the best approach to storytelling.

There are three types of verbs: Action, Stative, and Linking.

Action Verbs

These are your classic verbs. They describe what the subject of your sentence is doing. Action verbs are physical (like run, jump, write) but can also describe mental actions (like think, believe, dream). Action verbs give movement and create visual images. Example:

Marcus runs down the street.

Liora believes in the impossible.

See how those verbs bring the sentence to life? They let you know exactly what's going on.

Stative Verbs

Stative verbs describe a state of being or a condition rather than an action.

Unlike action verbs, which show movement or dynamic activities (like run, jump, write), stative verbs refer to situations, feelings, thoughts, relationships, or qualities that are more static and unchanging over a period of time.

Examples of Stative Verbs:

Verbs of Thinking or Belief: know, believe, understand, doubt, imagine, suppose.

She knows the answer.

I believe in your potential.

Verbs of Emotion or Feeling: love, hate, like, prefer, desire, fear.

He loves chocolate.

I hate waiting in line.

Verbs of Possession: have, own, possess, belong.

They own a beach house.

The book belongs to me.

Verbs of the Senses: see, hear, smell, taste, feel.

I see a bird in the tree.

This soup tastes great.

Verbs of Relationship or Identity: be, seem, appear, consist, include.

She is my friend.

The book seems interesting.

Stative verbs are usually not used in continuous or progressive tenses (-ing form). This is because they represent states or conditions that are not seen as having a clear beginning or end, unlike actions that can happen now. Example:

Incorrect: I am knowing the answer.

Correct: I know the answer.

However, some stative verbs can be used in continuous tenses when they take on a different meaning. For instance:

Normal use (stative): I think you're right. (think means "believe" here.)

Continuous use (action): I am thinking about what to do. (think refers to the active process of considering something.)

Why Are Stative Verbs Important?

Understanding the difference between stative and action verbs is crucial for using the correct verb tenses in your writing. Using a stative verb in the wrong form, especially in continuous tense, can make your writing feel awkward or incorrect. Stative verbs allow you to describe states of mind, conditions, and abstract concepts that make your characters and settings feel more complex and grounded.

Linking Verbs

Linking verbs don’t show action. Instead, they connect the subject of your sentence to more information about the subject. The most common linking verb is to be in all its forms (am, is, are, was, were, etc.).

Example:

Simone is terrified.

David was a hero.

Linking verbs help describe a state of being. They don’t do anything per se, but they help your reader understand more about your character.

Infinitive Forms of Verbs

The infinitive form of a verb is its most basic, uninflected form, usually preceded by the word to. In other words, it's the "to + verb" version, like to run, to write, or to eat. The infinitive isn’t tied to a particular subject, tense, or number — it’s the raw, neutral form of the verb. Example.

To jump over the fence was a challenge.

She wants to learn French.

He needs to call his mother.

There are two types of infinitives:

A Bare Infinitive: Verbs without the to (e.g., run, jump). They’re often used after certain verbs like can, should, make, and let.

I can run fast.

She made me stay late.

A Full Infinitive: This is the classic to + verb form.

He hopes to travel soon.

I want to read that book.

When Do We Use Infinitives?

Infinitives can be used in various ways:

As a subject. To travel is my dream.

As an object. He loves to dance.

To show purpose. She went to the store to buy groceries.

Verb Tense: Why It Matters

Tense tells the reader when something is happening: in the past, present, or future. Choosing the right tense keeps your story clear and helps your readers stay grounded in the timeline.

Past tense: He walked to the store.

Present tense: He walks to the store.

Future tense: He will walk to the store.

Most fiction is written in the past tense, but some writers experiment with present or even future tense to create a unique vibe.

Helping Verbs: The Sidekicks of the Verb World

Sometimes, verbs need extra help to fully convey what’s going on. Enter helping verbs, also known as auxiliary verbs. These verbs assist the main verb in expressing tense, mood, or voice.

Example:

Liora is running toward the ship. (Helping verb is helps express that the action is happening right now.)

Marcus has eaten the last slice of pizza. (Helping verb has shows that the action was completed.)

Helping verbs often include be, have, and do.

The Role of Adverbs: Modifying Verbs

Adverbs are words that modify or describe verbs (er, and other adjectives, or even other adverbs, but I digress.) They give us more detail about how, when, where, or to what extent something happens. They help clarify or intensify the action or description in a sentence. Most adverbs end in -ly (but not always).

Example:

Marcus runs quickly.

Liora sings beautifully.

Adverbs are like the spices of your writing. But be careful—too many adverbs can clutter your sentences. Instead of saying, “He ran quickly,” it might be better to say, “He sprinted.”

Common Questions Adverbs Answer:

How? – He ran quickly.

When? – She left yesterday.

Where? – They looked everywhere.

To what extent? – I'm completely exhausted.

Examples of Adverbs:

Modifying a verb: She quietly opened the door. (How did she open it? Quietly.)

Modifying an adjective: The cake is extremely delicious. (How delicious? Extremely.)

Modifying another adverb: He ran very quickly. (How quickly did he run? Very quickly.)

Types of Adverbs:

Adverbs of Manner – Describe how an action is performed.

Example: She sings beautifully.

Adverbs of Time – Indicate when something happens or for how long.

Example: We'll meet tomorrow.

Adverbs of Place – Show where the action occurs.

Example: He searched everywhere for his keys.

Adverbs of Frequency – Explain how often something happens.

Example: I always forget my umbrella.

Adverbs of Degree – Show the intensity or degree of something.

Example: The movie was really good.

The -ly Rule

A lot of adverbs are formed by adding -ly to adjectives. For example:

Quick → Quickly

Careful → Carefully

However, not all adverbs follow this rule. Some, like fast, hard, late, and well, are adverbs without the -ly ending.

Adverb Placement

Adverbs can be flexible regarding their position within a sentence, but their placement can affect meaning or emphasis.

Beginning of the sentence: Quickly, he ran to the store.

Middle of the sentence: He quickly ran to the store.

End of the sentence: He ran to the store quickly.

Notice how the meaning stays the same in each case, but the emphasis shifts depending on where the adverb is placed.

Watching Out for Adverb Overuse

While adverbs can add important detail, overusing them (especially -ly adverbs) can make your writing feel cluttered or weak. For instance, instead of writing "She spoke softly," you might choose a stronger verb like "She whispered."

Weak vs. Strong Verbs: The Writer’s Power Move

Strong verbs are one of the easiest ways to level up your writing.

Weak verbs are the ones that don’t pack much of a punch — words like is, are, has, and does. Strong verbs, on the other hand, are more specific and help paint a more vivid picture.

Weak verb:

She is walking to the door.

Strong verb:

She strides to the door.

See how the second sentence feels more dynamic? Strong verbs help your writing pop.

Choosing a better verb is a component of editing and proofreading. Sure, we can say Sally walked to the door, and there’s nothing mechanically wrong with that. However, if we’re trying to paint pictures with words, we must choose the best verb to describe the situation.

Sally sauntered to the door.

Sally sprinted to the door.

Sally dashed to the door.

Sally rushed to the door.

Each of these paints a very different picture.

How can you quickly distinguish an amateur writer from a pro? Everyone walks. Everyone whispers. Everyone falls. Everyone looks. Instead of editing their work to include the most robust verb possible, they’ll repeatedly reuse the same weak verbs. Watch for it.

A Quick Tip: Watch for Passive Constructions

We’ve all been there. You’re cruising along in your writing when suddenly — bam — you hit passive voice. Passive voice happens when the subject of your sentence isn’t doing the action. Instead, the action is being done to the subject.

Example of passive voice:

The book was read by Marcus.

Active voice:

Marcus read the book.

The active voice is more direct, more engaging, and generally preferred in fiction. If you want your readers to feel immersed in your story, aim for an active voice.

Put It All Together: A Verb-Driven Sentence

Let’s put everything we’ve learned together into a sentence. Here’s how to use action verbs, strong verbs, and adverbs to create a sentence that pops.

Weak sentence:

She is walking slowly toward the door.

Strong sentence:

She drags her feet to the door, hesitating before pushing it open.

Now, that’s a sentence that moves!

Wrapping Up

Verbs are the engine of writing.

They move your characters, set the pace, and bring your world to life.

Whether choosing between action, stative, linking verbs, or deciding if you need that adverb, remember that verbs are your secret weapon for writing stories that readers won’t be able to put down.

So, what are you waiting for? Go find the vibe in your verbs.

R

Understanding Nouns and Pronouns

Nouns are the building blocks of your sentences, bringing people, places, and things to life in your writing! Get cozy with them and elevate your prose!

Nouns.

The word comes from the Latin word nomen, which means "name."

It entered English through Old French as nom before evolving into the Middle English term noun. In its Latin root, nomen refers to any name or designation, which fits perfectly with what a noun does — name a person, place, thing, or idea.

Nouns are the cornerstone in the structure of a sentence; every sentence must have a noun. Every sentence needs a noun (or something that acts like one) because nouns provide the "who" or "what" the sentence is about. Without a noun, there's no subject or object to anchor the action or description — essentially, there’s nothing for the verb to "happen" to.

Types of Nouns

Common Nouns are your everyday, general nouns that refer to people, places, things, or ideas. They aren’t specific or capitalized. Examples: dog, city, book.

Proper Nouns are always capitalized and refer to specific names of people, places, or things. Examples: Fido, New York City, The Great Gatsby.

Concrete Nouns are things you can see, touch, smell, hear, or taste — anything physical. Examples: apple, ocean, music.

Abstract Nouns refer to intangible things — concepts, emotions, or ideas you can’t physically interact with. Examples: love, freedom, anger.

Collective Nouns are nouns representing a group of individuals or things. Even though they refer to multiple things, they’re treated as singular. Examples: team, herd, flock.

Countable Nouns are nouns you can count. They can be singular or plural. Examples: cat/cats, pen/pens.

Uncountable Nouns: These nouns refer to things that can’t be easily counted. You often treat them as singular. Examples: water, sand, information.

The Weight of a Noun

The more specific the noun, the more weight it carries. With more weight, the more convincing it is, adding credibility to the writer’s voice. What word is more attractive and interesting?

Mountain | Cliff

Fish | Trout

Wind | Breeze

Plant | Japanese Maple

Woods | Evergreens

Frequent use of generic terms rarely inspire. They may suffice by simply conveying a broad idea but aren’t good at conveying strong, mental pictures.

Here’s a generic sentence:

The man drove the car to the place.

Now, let’s rewrite it with stronger, more specific nouns:

The firefighter raced the SUV to the fire station.

And finally, even more specific.

The firefighter raced down Broadway in a Ford Explorer to the fire station.

The more specific the noun adds clarity and weight and paints a more vivid image. The reader can now picture exactly what’s happening. The more precise the nouns, the more your writing feels grounded, authentic, and engaging. That’s its weight.

Excessive Use of Nouns

Naturally, we could go overboard.

The firefighter in the bright red Ford Explorer with the oversized tires sped past the brick fire station near the crowded intersection on Broadway to the three-story warehouse engulfed in flames.

Yeah, too much — too much! Here, I’ve created a sentence overloaded with nouns. An excessive amount makes the reader slog through a verbal bog. Instead of specifics adding clarity, the excessive use of nouns creates an overflow of information akin to stuffing my mouth with three donuts at a time.

Let’s dig deeper. Here’s that list of generic nouns drilling down into very specific nouns.

Mountain | Cliff | Buttes

Fish | Trout | Brook Trout

Wind | Breeze | Gale

Plant | Japanese Maple | Sango-Kaku (a Coral Black Japanese Maple)

Woods | Evergreens | Norway Spruce

As a reader, I like specifics. Specifics lend more weight to the author’s voice.

Rex Thorne spurred his Mustang, urging her to race faster to the edge of the butte.

With specific words, I can paint a more vivid picture. But look at this:

Timmy cast his net into the Battle Ground Lake to catch some Brook Trout for dinner.

Hmm. A couple of issues here:

Do Brook Trouts live in lakes?

If Battle Ground Lake’s real (It is!), do Brook Trouts live there?

Are nets commonly used to catch Brook Trout?

If my story is either 1PL or 3PL from Timmy’s perspective, is he smart / wise enough to distinguish a Brook Trout from, say, a Rainbow Trout?

There’s a balance, isn’t there? To be credible, the author must select nouns appropriate for the setting and the character’s lens through which we experience the story.

Finding the Right Noun

Well, that’s our job as authors. We should look for the most specific nouns we can use in our sentences to add credibility and increase reader satisfaction. Unlike political figures, we can’t create facts willy-nilly. We must research! But we must also be faithful to the character and try to perceive the world through their lived experience.

Using Pronouns

Pronouns are words we use in place of a noun. Common pronouns include he, she, it, they, we, and you.

They’re shortcuts. Pronouns are more accessible, less formal references to the noun we’re talking about. They also serve as tools to reduce repitition. For example, instead of saying:

Sarah went to the store because Sarah needed milk.

You can say:

Sarah went to the store because she needed milk.

The pronoun she replaces Sarah in the second part of the sentence, making it flow better. It’s less … chunky … in the mouth, isn’t it?

There are different types of pronouns, like:

Personal Pronouns: I, you, he, she, it, we, they (referring to people or things)

Possessive Pronouns: mine, yours, his, hers, ours, theirs (showing ownership)

Reflexive Pronouns: myself, yourself, himself, herself, itself, ourselves, themselves (used when the subject and object of the verb are the same)

Demonstrative Pronouns: this, that, these, those (pointing to specific things)

Pronouns are great because they shorten sentences and make prose easier to read.

Abusing Pronouns

It happens all the time. The writer gets so caught up in their story that they constantly refer to their character as a pronoun rather than a name. It happens. The trick is to spot excessive degrees of pronouns and substitute an actual name to help balance out the read.

However, mechanical problems with pronouns occur frequently. Here’s an example:

Sarah told Emily that she needed to leave.

In this sentence, it's unclear who she refers to — does she mean Sarah or Emily? The reader has to guess, which can lead to confusion. This is an example of an unclear antecedent. An unclear antecedent happens when it's unclear which noun a pronoun refers to. The antecedent is the noun that a pronoun replaces, and when the connection between the two is ambiguous, it can confuse the reader.

Here’s a corrected, pretty version:

Sarah told Emily that Emily needed to leave.

And here’s a corrected, ugly version:

Sarah told Emily that she, Sarah, needed to leave.

Yuk! It’s technically correct, but it leaves a pasty sense on the tongue, right? The problem of unclear antecedent happens so frequently — so frequently — it is the number one mechanical issue I gripe about when editing or proofing someone’s draft.

Conclusion

So there you have it. Nouns. Simple things, yet kind of complicated.

Over time, writers will develop an artistic flair, using specific nouns to create a story's mood, tone, or atmosphere. Further, over time, writers will lean on specific nouns as a crutch, often (unconsciously) repeating the same detail in different works. And, over even more time, authors start to catch themselves in their repetitive noun choices, perform more research, and make adjustments. Watch for these subtle behaviors in your own writing.

R

Mastering the Basics - Spelling, Grammar, and Punctuation

Master your mechanics—spelling, grammar, and punctuation—so your stories shine and captivate readers without distraction! #WritingTips #NewAuthors

You’re an author.

You are Death, Life — a Creator of Worlds — and you’ve probably a slew of ideas racing around your mind.

Plots, characters, outlines, and timelines are all thrilling parts of the writing process and may consume your waking hours, but here’s the thing.

Before captivating your readers with a well-told yarn, you must nail down the basics.

To call yourself a writer, you must write and write well.

The Tools of Your Trade

Mechanics (spelling, grammar, and punctuation) are the bricks and mortar of your enterprise. They are your paint, brushes, chisel, and hammer. Words are the foundation that holds your writing together. You use them to paint vivid pictures, carve out meaning, and build connections with your readers. Great stories crumble to the earth without a solid grasp of mechanics.

As writers, when expressing our art, words are all we have.

There is nothing else.

What you remember from your 9th-grade English class is insufficient. Language is a fluid construct and is constantly evolving. If writing matters to you, and if you want your writing to matter to others, you will continuously be honing your skills. Writers work on mechanics all their lives.

Imagine showing up for an oil painting class, and you brought charcoal to work with. Delving deeper into that analogy, imagine a writer seeking publication is akin to a painter who shows up for an advanced oil painting class and doesn’t know the difference between sgraffito and impasto, feathering, blending, or glazing. Yikes. You’ve shown up ill-prepared because you lack fundamentals, the basic techniques.

Mechanics Are Tedious — Learn to Love Mechanics

So you might say practicing and improving upon mechanics may seem less glamorous than worldbuilding and storytelling, and you might be compelled to eschew my advice, thinking Grammarly or some other wiz-bang AI tool will be the magic pill that corrects your mechanical issues for you.

I’m sorry, but you're mistaken.

There’s no such thing as a magic pill.

If life hasn’t taught you that yet, you heard it from me first.

Like all things, you’ve got to put in the work.

In his book Outliers: The Story of Success, Malcolm Gladwell says 10,000 hours are needed (at a minimum) to become proficient at a skill.

Fellow writers and publishing editors expect a writer to grasp basic mechanics. They’re the essential tools in your toolbox. Otherwise, you’re the oddball out at the party, and ultimately, this is what you’re here for. Take mechanics seriously. Others do.

So the question becomes: do you want them to take you seriously? If you do, read on. If not, stop here and reconsider why you want to be a writer. You’ve got to love this stuff. Why are you here if you’re not impassioned to define a word, spell it correctly, and use it accurately every time? Trust me, your time’s better spent doing something else. There’s little fame or fortune in this business.

What Does It Mean to Be Thrown Out of a Story

Poor mechanics are the first issues that throw a reader out of a story.

Okay, so what does that mean?

Being "thrown out of a story" means that something in the narrative disrupts the reader’s immersion, pulling them out of the world the author has created.

A jarring spelling, grammar, or punctuation error forces the reader to stop reading. If you think about it, it’s like you’re riding a train, and suddenly, the train stops.

Heck, what happened? What went wrong?

When fully engaged in reading, readers get lost in a story, picturing the scenes, feeling the emotions, and connecting with the characters. But when a mistake or inconsistency occurs, it forces the reader to stop and re-evaluate, breaking the flow of their experience.

If a sentence is awkwardly structured or a comma is misplaced, it can confuse meaning, forcing the reader to pause to figure it out. However brief, that pause is enough to snap them out of the story's rhythm. It’s like hitting a speed bump while driving; it disrupts the smooth ride and makes you suddenly aware of the road again.

Fiction aims to immerse readers in the world you’ve built. When anything feels off, it risks "throwing them out" of the narrative, making it harder to re-engage and follow along with the same level of emotional investment.

Your goal as a writer is to prevent someone from being thrown off your train.

Publishing Editors

First, publishing editors are always right.

Swallow your pride. Don’t argue. It’s their publication, not yours. Stop fighting the wind.

Second, remember the first rule.

Third, if you’ve somehow forgotten the first and second rules, remember that the principal job of an editor is to verify that work is mechanically sound. It should seem reasonable that they don’t want their readers to have an unenjoyable reading experience. Nobody will publish illegible garbage, and who has the time to clean it up for you? Nobody. Who wants to convince you to clean something up? Nobody. Right. You’re catching on. They want to make that train ride as pleasant as possible.

Now, if an editor does return your manuscript for mechanical changes (remember the rules), think of their attention as a badge of distinction. It’s easy to dismiss someone; it’s harder to work with them. The editor might see promise in your material, so they took the time to request a cleanup because they thought the work mattered. Wow! What an honor! You weren’t round-filed. You were treated (gasp) like a professional.

So return the favor — do it! Clean up your mechanics and resubmit it, and if that same editor returns it to you again, remember the rules. Just do it. They’ve taken an interest, so learn something from the experience.

Breaking the Rules

While mastering mechanics is essential, there’s a time and place for breaking the rules to create a unique voice or style. Many authors bend or abandon conventions like grammar, punctuation, and sentence structure to capture a more authentic voice or evoke a particular mood.

Think of stream-of-consciousness writing, where punctuation might be sparse or erratic, reflecting thought's fast, often disorganized nature. Authors like James Joyce and Virginia Woolf are famous for using this technique, crafting a flow that feels natural, chaotic, or intimate, depending on the narrative’s needs. By breaking away from strict mechanical rules, writers can create a raw, unfiltered experience that draws readers deeper into their world.

However, breaking the rules successfully requires intention and control. It’s not about ignoring the basics but understanding them well enough to manipulate them effectively. Breaking the rules of mechanics can enhance the story’s voice, whether through run-on sentences that mimic a character’s anxiety or fragments that create a punchy, rhythmic narrative. Authors like Cormac McCarthy, who famously avoided quotation marks, create a minimalist, stark atmosphere that complements the tone of his stories.

But be careful — it’s risky. The key is knowing when to break the rules for impact, allowing the mechanics (or lack thereof) to serve the story rather than detract from it. Beauty is in the eye of the beholder, and every writer, judge, and editor will have an opinion on breaking mechanical rules to capture voice.

But Style Isn’t License

Let me help you.

Stop thinking this way.

You’re not that good.

Intentionally breaking the rules of spelling, grammar, and punctuation can create a distinct and creative writing style, but it’s not a free pass to disregard these conventions altogether. Successful rule-breaking is rooted in mastery; it comes from a deep understanding of how those rules work.

When writers deliberately bend or ignore mechanical norms, they achieve a specific effect: enhancing a character's voice, building a particular atmosphere, or conveying emotion. But it can backfire if done haphazardly, without care or purpose, leaving the reader confused, frustrated, or disengaged.

Breaking the rules effectively still requires respect for their role in clarity and communication. Readers need to feel grounded in the narrative, even if it is unconventional. If the writing feels sloppy rather than intentional, it risks alienating the reader or disappointing a publishing editor.

The key is to use these deviations sparingly and thoughtfully, ensuring they serve the story. Ultimately, creative writing isn’t about chaos; it’s about balance, knowing when to follow the rules, and when to push boundaries to enhance the narrative.

The Good News

The good news? Writing is a craft, and you can sharpen these skills every day!

Write. Every day. It should go without saying.

Read. All the time. That should also go without saying.

Proofread others in your writing group.

Volunteer for a contest or peer judging.

Make yourself available to other writers to edit their work.

Be kind and help others.

Every piece of writing is an opportunity to refine your mechanics.

It’s like polishing the lens through which readers experience your art.

Don’t waste another minute. Get out there, write, and write well.

R

Mechanical Notation in Writing

Master mechanical notations in writing to elevate your fiction! Parentheses, brackets, and more—learn how to use them effectively. #WritingSkills

All this month, I’ve been writing about breathing in writing and pacing: using punctuation to control how your story is interpreted. Today, I’ll be delving into mechanical notations that help the reader distinguish how to interpret a piece of text.

Mechanical notations are symbols that allow the reader to comprehend a subtext surrounding the words printed on the page. They signal your reader to interpret the words or phrases you’re about to present in a specific way.

Key Differences Between Punctuation and Mechanical Notation

Function.

Punctuation structures sentences, controlling the reading flow and clarifying the relationship between words and clauses.

Mechanical notations manage the text itself, providing additional layers of meaning, formatting, or editorial insight without altering the grammatical structure.

Usage.

Punctuation is essential to the readability and grammatical correctness of sentences.

Mechanical notations are more flexible, often adding style, tone, or clarity to specific parts of the text.

Grammatical Impact.

Punctuation directly affects how a sentence is interpreted grammatically.

Mechanical notations don’t usually change the grammatical structure; instead, they add extra information, emphasize certain elements, or provide clarity.

You’re already familiar with them, but let’s cover them just in case you might need a refresher.

Parentheses ( )

Parentheses are like whispers in your writing. It’s like I pulled you aside and included some relevant information in a quiet, confidential way. They add extra info without interrupting the flow, but beware — overuse can make your text feel cluttered. Use them sparingly to keep your writing clean and impactful.

Brackets [ ]

Think of brackets as your editorial voice. They’re great for clarifying or adding context to a quote. They’re not for everyday use, but they’re handy when you need them, like adding your own thoughts to a character’s internal monologue. They carry the weight of authority.

Curly Brackets { }

The curly brackets { } are also known as braces, and are not commonly used in traditional fiction writing, but they do have specific applications in other types of writing, particularly in technical, academic, or programming contexts. However, they can occasionally appear in fiction writing for specific purposes. Common use cases:

Grouping Information: In technical writing or mathematical expressions, curly brackets are often used to group multiple items together. For example, in a mathematical set: {2, 4, 6, 8}.

Programming. In computer programming, curly brackets define a block of code or group statements together in languages like C, Java, or JavaScript.

Stylistic Choices. Some experimental or avant-garde fiction writers might use curly brackets as a stylistic element. For instance, they could be used to enclose a character’s thoughts, a list of emotions, or abstract ideas to set them apart from the main narrative.

Fantasy or Science Fiction Contexts. In genres like fantasy or science fiction, curly brackets might be used to represent a special type of language, code, or communication between characters, especially if the communication is non-verbal or telepathic. Example:

The alien transmitted its thoughts directly into his mind: {Proceed with caution. The enemy is near.}

Creating a Distinct Visual Effect. Curly brackets could be used to create a visual distinction in the text, perhaps to indicate something out of the ordinary, such as a magical spell, a code being cracked, or a distinct part of a manuscript within the story.

Apostrophe ‘

Commonly used for contractions (can’t, won’t) or to indicate possession (John’s book). Apostrophes help keep sentences concise and show ownership or omission. Apostrophes can also be used to make letters or numbers plural in certain contexts, such as "Mind your p's and q's" or "There are two 7's in that number."

Quotation Marks " "

Quotation marks are your go-to for dialogue and highlighting specific phrases. They create clarity and structure in your narrative by outlining when a character begins to speak and ends speaking. They are used to enclose direct quotes from another source like, according to the author, "The sky was a brilliant shade of blue." Quotation marks can be used to enclose the titles of short works like poems, articles, short stories, or songs — "The Raven" by Edgar Allan Poe — and sometimes, quotation marks are used to draw attention to a specific word or phrase, often implying that it is being used in a non-standard or ironic way. Example:

The "expert" writer gave incorrect advice. That guy sucks!

Exclamation Points!

Excitement in a bottle! BANG! Zing! Wow! Exclamation points are perfect for showing strong emotions. But don’t go overboard. too many, and your writing starts to feel like it’s shouting at the reader. A little goes a long way. In fact, in my opinion, avoid using them at all in narration; save them for dialogue.

Question Marks?

These are the catalysts for curiosity. They’re essential for engaging readers and keeping them hooked. Questions can drive your plot forward, but overuse can make your characters seem indecisive and wishy-washy.

Understanding these tools can elevate your writing and help you communicate more effectively. Practice using them in your drafts, and soon they’ll become second nature.

R

#WritingTips #FictionWriting #NewAuthors

The Art of Breathing in Your Writing

Master the art of pacing by using pauses in your writing. Learn how to control the rhythm and impact of your story with these simple techniques.

This whole month, I’ve illustrated how to use punctuation to control pacing through breathing in your writing.

No, I’m not talking about literal breathing — although, I assure you, that’s important, too — but rather how the rhythm of your writing controls the pace, the pauses, and ultimately, the impact of your story.

Explaining Pacing in Writing

Pacing in writing refers to the speed at which a story unfolds, guiding the reader through the narrative at a rhythm that enhances the experience.

Pacing is a crucial element of storytelling because it controls the flow, influencing how readers perceive the events, characters, and emotions in your story. It’s like the heartbeat of your narrative. Fast pacing can build excitement and tension; slow pacing allows for reflection and emotional depth.

The key to mastering pacing is understanding how to use pauses effectively. Pauses are the breaths in your writing — they give your reader a moment to absorb what’s happening and prepare for what’s next.

Pacing Ideas and Concepts

1. Pacing and Genre.

Different genres have different pacing expectations. Action-packed thrillers often have fast pacing, with short sentences and quick transitions to maintain excitement and suspense. On the other hand, literary fiction might have a slower pace, allowing for detailed character exploration and thematic development. Understanding your genre’s typical pacing can help you meet reader expectations.

2. Sentence Structure and Pacing.

One of the most direct ways to control pacing is through sentence structure. Short, choppy sentences can create a sense of urgency, making the reader feel like things are happening rapidly.

He ran. The door slammed. Silence.

This structure conveys speed and tension. Conversely, longer, more complex sentences can slow the pace, encouraging readers to take their time and absorb the details:

He ran through the darkened hallways, the sound of his footsteps echoing off the cold stone walls — the door creaked shut behind him, plunging the room into an eerie silence.

3. Pacing through Dialogue.

Dialogue can significantly impact pacing. Rapid-fire exchanges between characters can speed up the pace, especially during arguments or high-stakes situations. Pauses between lines, indicated by ellipses or dashes, can create tension and slow down the pace, making readers hang on to every word.

4. Pacing with Action and Description.

Action scenes are usually fast-paced, with less description and more direct movement. They keep readers on the edge of their seats, racing through the narrative to see what happens next. However, to prevent exhaustion, action scenes are often balanced with slower-paced sections that provide descriptive detail, character introspection, or world-building.

5. Pacing through Chapter and Scene Breaks.

Where you choose to end a chapter or scene can also affect pacing. Cliffhangers create a quick, dramatic end, urging the reader to continue. In contrast, a chapter that ends on a reflective note can give readers a chance to pause and consider what they’ve read.

6. Varying Pacing for Impact.

Effective storytelling often involves varying the pace to maintain reader interest. A story that’s too fast all the way through can be exhausting, while a story that’s too slow can be dull. By mixing fast-paced action with slower, more contemplative moments, you create a dynamic rhythm that keeps readers engaged.

7. Pacing and Reader Emotion.

Pacing isn’t just about speed; it’s also about controlling the emotional impact of your story. A slower pace can give readers time to connect with characters and feel the weight of their experiences. A faster pace can heighten the intensity of action or drama. By understanding how pacing affects emotion, you can better control how your readers feel as they move through your story.

8. Pacing and Plot Development.

Regarding plot, pacing is about deciding how quickly events unfold and how much time you spend on different parts of the story. For example, a slower pace might be used to build suspense before a major plot twist, while a faster pace might be used to rush toward the climax. Balancing these elements is key to maintaining momentum and interest throughout your story.

Controlling Pacing With Punctuation

And now, we come full circle. Ellipses, periods, hyphens and dashes, em-dashes, en-dashes, colons, semi-colons, commas, and Oxford Commas.

Punctuation marks are your best friends when it comes to creating these pauses. A well-placed comma or a thoughtful em-dash can slow down the reader just enough to highlight a crucial point or create suspense. Ellipses … linger in the moment, feeling the weight of what’s unsaid. Periods are the full stops, giving your readers a chance to take a breath and process the sentence before moving on.

The beauty of using pauses is that it gives you, the writer, control over the reader’s experience by indicating to the reader when to take a breath. You can guide them through your story at the pace you want, rushing through action scenes or slowing down for heartfelt moments.

So, don’t be afraid to experiment with pacing. Play with pauses, vary your sentence lengths, and watch how the rhythm of your story transforms.

R

The Oxford Comma: Friend or Foe?

Wondering if you need the Oxford comma in your writing? Discover why this tiny punctuation mark could be your new best friend!

Ah, the Oxford comma! A tiny and rather misunderstood punctuation that causes a surprisingly big debate amongst editors.

Ye Olde Oxford Comma

The expression "Oxford comma" comes from its association with the Oxford University Press, a prestigious publishing house linked to the University … of Oxford. Duh.

The association dates to the early 20th century when the Oxford University Press’s style guide (often referred to as "Hart's Rules," first published in 1893 by Horace Hart, who was the Controller of the Oxford University Press) advocated for the use of the serial comma to avoid ambiguity in writing.

People thought the name was catchy, so yeah, here we are.

The term became widely recognized because the Oxford style guide insisted on this punctuation to ensure clarity in writing, especially in complex lists where the meaning could be ambiguous without the comma.

Cool. But What Does It Mean To Me?

If you’re a new author, you’ve probably come across the Oxford comma — sometimes called the serial comma — and wondered, "Do I really need this?"

Hmmm … maybe?

The Oxford comma comes before the "and" in a list of three or more items. Example:

I packed my bags, my camera, and my notebook.

Without the Oxford comma, it reads:

I packed my bags, my camera and my notebook.

Sure, it’s a small mechanical difference, but it translates to a world of difference in clarity and meaning.

Please consider this classic example:

I’d like to thank my parents, Oprah Winfrey and God.

Without the Oxford comma, it sounds like your parents are Oprah and God. That’s pretty awesome but probably not what you meant.

By adding the Oxford comma, it becomes clear that you’re thanking three separate entities:

I’d like to thank my parents, Oprah Winfrey, and God.

Hey, look, ma — it’s a list!

Okay, Brass Tax and Donuts: What’s the Technical Difference Between an Oxford and a Regular Comma?

A “regular comma” is any comma used according to standard punctuation rules, which includes separating elements in a sentence, such as items in a list, clauses, or adjectives. An example again:

I packed my shoes, my hat and my jacket.

You use an Oxford Comma in a list of three or more items. The Oxford Comma is the comma placed immediately before the coordinating conjunction (usually "and" or "or") in a list of three or more items. Vualla:

I packed my shoes, my hat, and my jacket.

Here, the Oxford comma is the one after "hat."

It’s more readable, wouldn’t you say?

Why Use It?

Well, some style guides require it, whereas others do not.

Style Guides that Prefer the Oxford Comma:

The Chicago Manual of Style: Strongly advocates for the Oxford comma, especially in complex sentences, to ensure clarity.

APA (American Psychological Association): Also recommends using the Oxford comma in academic writing to avoid potential confusion.

MLA (Modern Language Association): Prefers the Oxford comma for similar reasons, especially in scholarly works.

Style Guides that Don't Require the Oxford Comma:

AP (Associated Press) Style: Generally does not require the Oxford comma, except in cases where its absence would lead to ambiguity. The AP style is commonly used in journalism and by news organizations.

The New York Times Stylebook: Follows a similar approach to AP, often omitting the Oxford comma unless it's necessary for clarity.

Editor Preferences:

Clarity and Consistency: Many editors prefer the Oxford comma because it prevents misinterpretation and awkward sentences. They see it as a simple way to ensure that a sentence's meaning is clear.

Style Guide Adherence: Editors often follow the preferred style of the publication they are working with, so their use of the Oxford comma might be determined by the house style rather than personal preference.

Flexibility: Some editors adopt a flexible approach, using the Oxford commas when it adds clarity but omitting them when the sentence is straightforward.

While some styles don’t require it, and it’s not a hard rule, using the Oxford comma can often save you from potential confusion.

So, should you use the Oxford comma? My opinion: you should, yes, most of the time! It’s a simple way to keep your writing sharp and your meaning clear. Plus, it’s one of those small details that can set you apart as a careful, thoughtful writer.

R

#WritingTips #OxfordComma #NewAuthors

Behold! The Mighty Comma, Colon, and Semi-Colon

Master the comma, colon, semi-colon, and period to elevate your writing and make your sentences breathe.

For weeks now, I’ve been talking about breathing in your writing.

Pausing and waiting — bridging ideas with dashes or slowing the reader down to emphasize something, like when something dark and sinister waits for them just around the corner.

Today, we’re talking about the most common nitty-gritty punctuation tools: the comma, colon, semi-colon, and period. These little marks can make a big difference in your writing, but they can also trip you up if you're not careful.

Let’s break them down in a friendly, no-fuss-no-muss way.

The Comma (,)

Think of the comma as the humble sidekick of punctuation. It's there to help you out, making your sentences clearer and your lists tidier. Use commas to separate items in a series:

I packed my bag with a notebook, a pen, and a sandwich.

They also help when you’re linking independent clauses with conjunctions:

Yeah, I wanted to write a novel, but I decided to write short stories instead.

The Colon (:)

The colon is like a drumroll. It introduces lists, quotes, explanations, or a punchline.

She had one goal: to become a published author.

Notice how it sets the stage for something important? When using colons, make sure what comes before it is a complete sentence on its own.

The Semi-Colon (;)

Ah, the semi-colon — oh man, I love these guys! Often misunderstood yet incredibly useful, the semi-colon is a bridge between closely related ideas. Think of it as stronger than a comma but not as final as a period.

I love writing flash fiction; it allows me to tell powerful stories with fewer words.

But the semi-colon is so much more!

Clarifying Complex Lists: When listing items that include commas, a semi-colon helps avoid confusion.

Example: "The conference will feature talks by Jane Smith, an author; John Doe, a publisher; and Alice Brown, a literary agent."

Explanation: The semi-colons separate the list items clearly, preventing misreading.

Balancing Lengthy Clauses: A semi-colon can balance lengthy clauses within a sentence, making it easier to read. For example:

Example: "He traveled the world searching for inspiration; she found hers in the everyday moments."

Explanation: The semi-colon maintains the balance and flow between the lengthy, related clauses.

Sure, semi-colons are super cool, but they’re often abused. Some writers (ahem, is it hot in here?) fall in love with the semi-colon and start using it everywhere. This can make your writing seem choppy or overly formal. Remember, it’s a special tool — a conjoining tool — and not a default punctuation mark.

Misconnecting Clauses: A common mistake is using a semi-colon where a colon or comma would be more appropriate.

Example: "I bought a new laptop; because my old one was too slow."

Explanation: The second clause is not independent; a comma or a full stop would be better.

In Lists Without Internal Commas: Using semi-colons in simple lists where commas suffice can confuse readers.

Example: "She bought apples; oranges; and bananas."

Explanation: Commas would work perfectly here, and semi-colons are unnecessary.

The Period (.)

The period is the full stop in your writing. It’s the punctuation mark that brings a sentence to a close. The period is simple and powerful; it lets your readers know that a thought is complete.

Writing is both an art and a craft.

It gives your readers a clear pause and signals that you’re moving on to a new idea.

Mastering punctuation marks can elevate your writing and make your sentences breathe. But then there’s the art of bending all of these rules to create a distinct, unique voice in your reader's mind.

Stream of Consciousness

Stream of consciousness is a narrative style that attempts to capture the flow of thoughts and feelings. Writers like James Joyce and Virginia Woolf often use punctuation creatively to mimic the inner workings of the mind, like:

Long, run-on sentences: To reflect a character's unfiltered thoughts.

Example: "She walked along the beach feeling the wind in her hair and the sand beneath her feet and the sound of the waves crashing and the seagulls calling."

Minimal punctuation: To create a sense of immediacy and immersion.

Example: "The night was dark and the road was long and her heart was heavy and she kept walking and walking and walking."

Ellipses and Dashes

Ellipses (…) and dashes (—) are powerful tools for creating pauses, breaks, and interruptions in dialogue and narrative. They can convey hesitation, suspense, or a sudden change in thought. For instance:

Ellipses: Indicate a trailing off or an unfinished thought.

Example: "I just don't know if I can…"

Dashes: Create emphasis or an abrupt shift.

Example: "She reached for the door — and stopped when she heard the noise."

Lack of Punctuation

Some writers, like Cormac McCarthy, are known for their sparse use of punctuation. This minimalist approach can create a unique, rhythmic prose that feels raw and immediate. For example:

No quotation marks in dialogue: To blend dialogue with narrative seamlessly.

Example: "Are you coming with me he said She shook her head No I can't"

Sparse commas and periods: To maintain a steady, flowing pace.

Example: "He walked through the desert the sun beating down the sand stretching endlessly"

Innovative Uses of the Semi-Colon and Colon

Writers like George Orwell and Kurt Vonnegut have used semi-colons and colons to great effect, creating emphasis and rhythm in their prose. For example:

Semi-colon for dramatic effect:

Example: "He knew what he had to do; there was no other choice."

Colon for emphasis:

Example: "There was one thing she feared most: failure."

Breaking the Rules for Voice

Sometimes, breaking punctuation rules can help convey a character's unique voice or the tone of a narrative. For example:

Using commas for breathless narration:

Example: "And then, she ran, faster than she'd ever run before, because if she stopped, even for a second, it would all be over."

Capitalization for emphasis:

Example: "He realized then that THIS was the moment he'd been waiting for."

Short, Stabby Sentences

And, myself, I’m a fan of the short, stabby sentence to create a sense of tension and drama. It’s the volleyball spike to end the game.

I’ve said enough.

Punctuation is a tool, and like any tool, its effectiveness depends on how you use it. By understanding and occasionally breaking the rules, you can craft prose that is uniquely yours, adding depth and emotion to your writing. So go ahead, experiment — breathe, and let your unique voice be heard!

R

#WritingTips #NewAuthors #PunctuationPower

Mastering the Ellipsis

Learn how to use ellipses effectively in your writing and avoid common pitfalls with our easy guide for new authors.

Okay! The last time around, I walked you through using em-dashes in dialogue. This week, we’re still on the concept of pausing, but we will discuss the ellipsis.

An ellipsis, or ellipses in the plural, is a punctuation mark of three dots. It generally represents an omission of words or leaving something unsaid. It’s a hesitant or dramatic pause in dialogue, a trailing off, a natural conversational element.

You’re familiar with it. It looks like this: (...) unless you agree with the Chicago Manual of Style (CMOS), which suggests it should look like this: (. . .) — three dots separated by spaces.

“Jenny, there wasn’t a time where . . . I’m sorry. Did you say something?”

Did you catch the preceding space between ‘where’ and ‘I’m’? Yeah, that’s also CMOS. Coincidentally, CMOS also says there shouldn’t be a space when ending with punctuation. Here are some funky CMOS examples:

This ellipsis … is in the middle of a sentence.

This one is at the end. … Note the space after the period.

A comma precedes this ellipsis, … with similar spacing.

What do you mean? … More of the same.

But when punctuation follows …, close it up to the ellipsis.

Is that wise …? We think so.

Even more confusing, some word processors auto-transform an ellipsis into an ASCII character.

Mechanically, an ellipsis can capture hesitation and pause perfectly in dialogue. For example:

"Well, I thought we could go to the park . . . if you want."

See how it leaves the sentence hanging, inviting the reader to fill in the blanks? It's a subtle way to add depth to your characters and their interactions.

It’s a Trap!

That said, too many writers fall into a common trap: abusing ellipses.

Sure … it sounds natural … but when recreating … the sound of speech in their heads … the writer creates an abundance of pauses … that translates to too many dots on the page … or … becomes a truly lazy way … to connect sentences. Sometimes, you trail off for no reason …

It's easy to get carried away, but too many ellipses can make your writing seem fragmented and your characters overly hesitant or unsure.

It’s Clutter!

When I read a passage in a book, I don’t want to trip over things left on the floor, step around objects, or take a running jump to get to the conclusion of a paragraph. Ellipises are white noise gaps that don’t need to be present in every paragraph, thought, or monologue.

It's like cursing or too many exclamation marks — less is often more.

It’s Tedious and Trite!

Whether you’re writing for contests or not, I presume you want your writing to stand out. You don’t want it to feel amateur or stumbling, or, howdy-hum-dum boring. So, here’s my advice: don’t.

Avoid using the ellipsis.

If you must, use it very sparingly, and only in dialogue.

When using it in dialogue, imagine your character placing their thumb against their chin and staring thoughtfully out into space. Then, consider, Jedi: Is that the pause you’re looking for? Would an em-dash, comma, or semi-colon be more effective?

When writing a narrative, ellipses can indicate a time jump or an unfinished thought. They create a sense of mystery or suspense, but again, use them sparingly. A well-placed ellipsis can add intrigue, but overdo it, and your readers or a judge might find it distracting.

So, what's the takeaway? Use ellipses to enhance your dialogue and narrative, but don't rely on them too much. Keep your writing clear and concise, and your readers will thank you.

R

How to Use Em-dashes in Dialogue

Learn how to use em-dashes in dialogue to add realism and depth to your characters' conversations. #WritingTips #DialogueMagic

The other day, I wrote about how em-dashes differ from commas and last week, I wrote about the distinction between em-dashes, en-dashes, and hyphens.

Today, let’s talk about how to use em-dashes in dialogue.

If you're new to writing or just looking to refine your skills, this little punctuation mark can add dramatic emphasis to your characters' conversations.

Interruptions and Cut-offs

One of the most common uses for em-dashes in dialogue is to indicate interruptions or cut-offs. It shows that a character’s speech is abruptly stopped by someone else or by an event.

“I don’t think you should —”

“No, you listen to me!”

Notice that’s not a hyphen (-), and, in this case, the em-dash clearly shows that the first character was cut off mid-sentence.

Sudden Changes in Thought

Em-dashes are also great for showing a character’s sudden change in thought or self-interruption. This can make your dialogue feel more natural and spontaneous. For instance:

“I was just thinking — oh, never mind. It’s not important.”

Here, the em-dash adds a realistic pause, giving the impression of a natural, off-the-cuff conversation.

Adding Afterthoughts or Clarifications

An em-dash can introduce an afterthought or clarification, making the dialogue feel more natural and spontaneous:

“He’s my brother — my half-brother, actually.”

Adding Emphasis

Sometimes, a character might want to emphasize a point or add an afterthought. An em-dash can help you achieve this:

“I swear I saw it — a ghost, right there in the hallway!”

The em-dash highlights the dramatic reveal, adding a punch to the dialogue.

Creating Suspense

An em-dash can be used to create suspense by cutting off a character’s speech right before an important reveal:

“I know who the killer is — it’s —”

Introducing a Sudden Realization

Use an em-dash to show when a character suddenly realizes something mid-sentence:

“We could always — wait, did you hear that noise?”

Correcting Oneself

When a character starts to say something and then corrects themselves, an em-dash can help illustrate this shift:

“We should meet at the — no, wait, let’s go to the café instead.”

Emotional Outbursts

We can use an em-dash to denote surprise and heightened emotional states:

“I can’t believe you did that — how could you betray me like this?”

Give it a try. Experiment with em-dashes in your dialogue. They can add a lot of depth and realism to your characters’ conversations.

R

#WritingTips #DialogueMagic #NewAuthors

An Em-dash vs. Comma: What's the Difference?

Learn when to use an em-dash vs. a comma to control the pace and tone of your writing. #WritingTips #PunctuationMatters

Hey!

Last week, I wrote about the distinctions between an em-dash, an en-dash, and a hyphen.

But if you’re a budding writer and want to polish your prose, you've probably encountered a tedious mental debate: When should I use an em-dash instead of a comma?

These two punctuation marks can change the rhythm and clarity of your sentences, so let's explain them in a friendly, easy-to-understand way.

The Em-Dash (—)

The em-dash is like a sudden breath in your writing. An interruption. It creates a dramatic pause or an abrupt change in thought. It's longer than a hyphen and a bit more versatile. Use it to add emphasis or to insert additional information that you want to stand out.

The cake — a triple-layer chocolate masterpiece — was the highlight of the party.

Here, the em-dash makes the description pop, giving it extra weight and attention.

Also, you may wonder if there should be a space between the first and last words in an em-dash. In the previous example, you see I added an extra space between “cake” and “a,” and “masterpiece” and “was.”

Most American style guides, like The Chicago Manual of Style and The Associated Press (AP) Stylebook, recommend using em-dashes without spaces.

The cake—a triple-layer chocolate masterpiece—was the highlight of the party.

However, some style guides, especially in British English, recommend using spaces around em-dashes.

The cake — a triple-layer chocolate masterpiece — was the highlight of the party.

Ultimately, consistency is key. Pick a style and stick with it throughout your document. For most American English writing, it’s standard to use no spaces around em-dashes. The big takeaway is to do as you please but be consistent — avoid drawing attention to inconsistencies.

The Comma (,)

The comma, on the other hand, is the everyday pause of punctuation. It provides a gentle pause, helping to clarify the structure of your sentences and separate elements. Use it to list items, separate clauses, or add slight pauses in your writing. It indicates to the reader, “When to take a breath.”

The cake, a triple-layer chocolate masterpiece, was the highlight of the party.

In this sentence, the commas offer a smooth, flowing pause, giving the reader time to digest the information without any dramatic flair.

When to Use Which?

The key difference lies in the impact you want to create. Use an em-dash when you want to emphasize or highlight something important. It’s perfect for adding a bit of punch to your prose. Use a comma when you need a subtle, less interruptive pause. It’s ideal for keeping your writing clear and easy to follow.

Abusing the Em-Dash

Oh, good sir, nothing infuriates me more.

It’s totally possible to overuse the em-dash just like any other punctuation mark. While the em-dash is a powerful tool that can add emphasis, drama, or a sudden change in thought, relying on it too much can make your writing seem choppy or overly dramatic.

Here are a few ways em-dashes can be overused:

Overemphasis

Using em-dashes too frequently can dilute their impact, making every sentence seem overly dramatic or important, which can tire the reader.

Lack of Variety

Good writing often requires a mix of punctuation marks to create rhythm and flow. Overusing em-dashes can make your writing feel monotonous or one-note.

Confusion

Too many em-dashes can confuse readers, making it harder for them to follow your train of thought or understand the structure of your sentences.

Example of Overuse

The cake — a triple-layer chocolate masterpiece — was the highlight of the party — and everyone agreed — it was the best they'd ever had — even better than the bakery's famous cookies — which were also delicious.

Example of Balanced Use

The cake — a triple-layer chocolate masterpiece — was the highlight of the party. Everyone agreed it was the best they'd ever had, even better than the bakery's famous cookies.

Alternatives to Em-dashes

To avoid overuse, consider mixing in other punctuation marks:

Commas for slight pauses and lists.

Colons for introducing lists or explanations.

Semicolons to link closely related independent clauses.

Parentheses for adding supplementary information without the dramatic flair of an em-dash.

By mastering these tools, you'll be able to control the pace and tone of your writing, making your stories even clearer and more engaging. Rock on.

R

#WritingTips #PunctuationMatters #NewAuthors

Em-dash, En-dash, and Hyphen: A Quick Guide

Learn the differences between em-dash, en-dash, and hyphen to add clarity and style to your writing. #WritingTips #PunctuationPower

True, punctuation — like dashes — can add flavor to your writing, but let’s get the dashes right. Not all dashes are created equally, and they have different uses and meanings. You may not realize it, but there are three dashy distinctions we need to work on as new authors.

Let’s get to it!

Em-dash (—)

The em-dash is called an em-dash because its width is approximately the same as the height of the capital letter "M" in the font set. This convention dates back to the days of typesetting when the dash's size was physically measured against the letter "M" on the typesetting blocks. Thus, "em-dash" refers to the comparable length of the dash. But what does it mean?

The em-dash is the drama queen of punctuation. It's long and loves to make an entrance, creating a pause that grabs your reader's attention. Use it to add emphasis, break thoughts, or insert an aside — just like this. It’s the length of an “M” (hence the name) and is perfect for those moments when you want to make a statement.

Most word processors translate a double hyphen as an em-dash and insert the ASCII symbol (—) rather than (--).

Here’s the skinny on how to create an em-dash in Windows.

Method 1: Using Keyboard Shortcuts

Alt Code: Hold down the

Altkey and type0151on the numeric keypad (not the numbers at the top of your keyboard). Release theAltkey, and the em-dash will appear.

Method 2: Using Microsoft Word

AutoFormat: In Microsoft Word, you can type two hyphens (

--) and then press the spacebar or continue typing, and Word will automatically convert it into an em-dash.Insert Symbol: Go to the "Insert" tab, click "Symbol" on the far right, choose "More Symbols," find the em-dash in the list, and click "Insert."

Method 3: Using Character Map

Character Map Application: Search for "Character Map" in the Windows search bar and open the application. Find the em-dash in the list, select it, click "Select," and then "Copy." You can now paste the em-dash wherever you need it.

Method 4: Using Unicode

Unicode: Type

Ctrl+Shift+u, then type2014, and pressEnter(this works in certain applications that support Unicode input, such as some text editors).

Here’s how to create an em-dash on a Mac.

Method 1: Using Keyboard Shortcuts

Keyboard Shortcut: Press

Option(orAlt) +Shift+-(hyphen key). This will insert an em-dash directly into your text.

Method 2: Using Microsoft Word

AutoFormat: In Microsoft Word for Mac, you can type two hyphens (

--) and then press the spacebar or continue typing, and Word will automatically convert it into an em-dash.Insert Symbol: Go to the "Insert" menu, select "Symbol," then "Advanced Symbol," find the em-dash in the list, and click "Insert."

Method 3: Using the Character Viewer

Character Viewer: Click the "Edit" menu and select "Emoji & Symbols" (or use the shortcut

Control+Command+Space). In the Character Viewer, type "em dash" in the search field, find the em-dash, and double-click it to insert it into your text.

And here’s how you create an em-dash in Google Docs.

Method 1: Using Keyboard Shortcuts

Keyboard Shortcut: On a Windows computer, press

Alt+0151on the numeric keypad. On a Mac, pressOption(orAlt) +Shift+-(hyphen key).

Method 2: Using the Special Characters Menu

Special Characters:

Place your cursor where you want the em-dash.

Go to the "Insert" menu.

Select "Special characters."

In the search box, type "em dash" and it will appear in the grid below.

Click on the em-dash symbol to insert it into your document.

Method 3: Using Auto-Replace

Auto-Replace:

Go to the "Tools" menu and select "Preferences."

In the "Automatic substitution" section, type a unique text string that you want to replace with an em-dash, such as

--.In the "Replace with" field, paste an em-dash (you can copy one from another document or use the Special Characters menu to get one).

Click "OK" to save the preference.

En-Dash (–)

The en-dash, being about half the width of an em-dash, gets its name similarly from its size relative to the letter "N." The en-dash is a bit more modest, shorter than the em-dash but longer than a hyphen, and is typically used to indicate a range, like “1990–2000” or “pages 45–50.” Think of it as a connector, bridging elements together smoothly.

On Windows (Microsoft Word):

Keyboard Shortcut: Press

Ctrl+-(on the numeric keypad). This will insert an en-dash.Insert Symbol:

Go to the "Insert" tab.

Click "Symbol" on the far right.

Choose "More Symbols."

In the Symbol dialog box, find the en-dash in the list, select it, and click "Insert."

On Mac:

Keyboard Shortcut: Press

Option+-(hyphen key). This will insert an en-dash.Insert Symbol:

Go to the "Insert" menu.

Select "Symbol," then "Advanced Symbol."

Find the en-dash in the list and click "Insert."

In Google Docs:

Keyboard Shortcut:

On a Windows computer, there is no direct shortcut for an en-dash, but you can use the Special Characters menu (see below).

On a Mac, press

Option+-(hyphen key).

Special Characters:

Place your cursor where you want the en-dash.

Go to the "Insert" menu.

Select "Special characters."

In the search box, type "en dash," and it will appear in the grid below.

Click on the en-dash symbol to insert it into your document.

Auto-Replace:

Go to the "Tools" menu and select "Preferences."

In the "Automatic substitution" section, type a unique text string that you want to replace with an en-dash, such as

--.In the "Replace with" field, paste an en-dash (you can copy one from another document or use the Special Characters menu to get one).

Click "OK" to save the preference.

Hyphen (-)

Finally, the hyphen is the author’s workhorse. It’s the shortest of the trio and is used to link words, forming compound terms like “well-being” or “mother-in-law.” It’s straightforward, functional, and gets the job done without any fuss.

Why Does This Matter?

Using these dashes correctly can enhance the clarity and style of your writing. Imagine crafting a beautiful sentence, only to have a contest judge/reader stumble because of a misplaced hyphen for an em-dash. By mastering these, you’ll polish your prose and keep your readers hooked.

So, hop to it! The next time you're writing, remember the roles these dashes play. Your story — and your readers — will thank you for it!

R

#WritingTips #PunctuationPower #NewAuthors

I’m An Amazon Best Seller!

Anyone can use free book promotions to advance to an Amazon Best Seller list. Here’s how I did it.

Hey, look, Ma - I’m a #1 Amazon Best Seller!

Well … kinda.

And not just in the 45-Minute Science Fiction & Fantasy category, either. Look at these Amazon Best Seller Ranks (BSR’s) for my title, Eyes of Memory.

I’m enjoying a lot of visibility in three critical categories. The book is being splashed in front of thousands of people looking at best-seller lists on Amazon at this very moment. Hurrah! I’ve overcome the long tail!

But how did I do this? And how much did it cost?

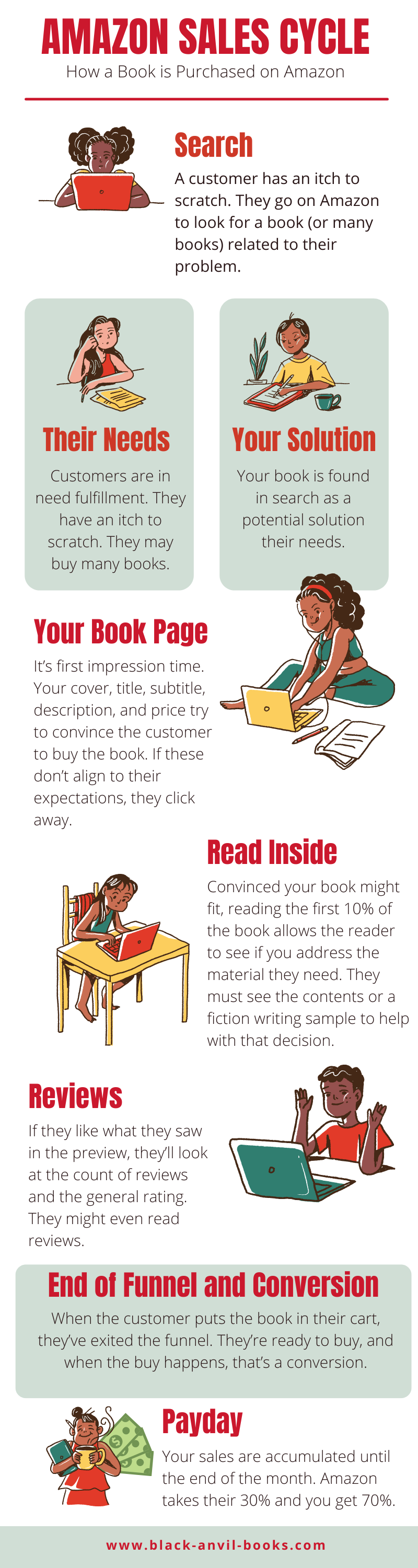

In previous posts, I’ve written about the Amazon Sales Cycle and how the Amazon referral engine responds to positive feedback loops. When Amazon sees your title moving in traffic and sales, it does its best to promote it to others. More sales, more feedback.

Every month, I give away a story I’ve published on Amazon for five days. I market that giveaway using my email mailing list, social media (Facebook and Instagram), and Bookdoggy.com. I used a promo code Bookdoggy is running until May 10, to lower their $24/listing to a $12/listing.

That generated a bunch of freebie sales for the title, launching the referral engine. A freebie sale is a sale in Amazon’s algo, which pushed my title to the top of these lists.

But my strategy isn’t just to be read for free and forgotten. Here’s a breakdown of last two days:

Here, you can see that the freebie inspired additional impulse buys from my catalog, but take a look at last month’s results:

What’s important is seeing how the freebie offering inspired more commercial sales from other titles and more KENP reads. I’m finding that the wider my catalog and offerings, the more sales and KENP reads follow the monthly freebie promotion.

When running a similar campaign, look for secondary effects like your website metrics to shift. Here, I got a jump from my regular traffic to my website, increasing brand + product visibility.

Beyond just visits, I want to make sure that the landing page for the title I’m featuring is receiving the new traffic. Checking my engagement numbers, that’s exactly what I’m seeing. Eyes of Memory is the second-most frequented page on the site, behind the main page (Portfolio).

Here’s the takeaway:

A freebie sales strategy combined with a social and newsletter strategy can help temporarily boost your BSR.

It gives you premium visibility in the category, putting you in front of potential readers for a short time.

If your title converts an Amazon shopper, they may return to your catalog to purchase more titles at their regular price.

If your title is enrolled in Amazon’s Kindle Unlimited (KU) program, the campaign may create a buzz that attracts new KU readers.

More readers that come to your website is an upsell opportunity, but also, a funnel/capture opportunity. Maybe they’ll subscribe to you, or follow you on social media. Those secondary effects are just as important as sales.

Alas, the results are fleeting. I’ll only be at the top of these lists for a few days while my promotion runs, and, gradually, by the hour, my number one will slip away and send the title back into BSR obscurity.

Still, after this, I hope to see more commercial unit sales and KEMP reads, social media likes or follows, website visits, and newsletter subscriptions. That will help improve my numbers for the next campaign.

You can do this, too!

R

Understanding the Amazon Sales Cycle

Master the Amazon sales cycle: Convert clicks into sales! Learn how to optimize your book's visibility and entice buyers effectively.

If you’ve been following my recent blog posts, I’ve been spending time educating myself on selling books on Amazon. I figured I’d document my process to help other self-publishers like me.

Earlier, I’ve talked about the importance of understanding the long tail. Amazon’s book catalog is 32.8 million entries deep, with thousands of new books uploaded daily to the platform. Visibility is an enormous problem. Knowing your audience is paramount: how will they look for your product? How does your book scratch their itch?

One way to overcome the problem is to ensure your descriptions and keywords match what people are searching for. That’s an organic technique where you research keywords and phrases people will use to find your book; you might even use those keywords in the book's title and subtitle to improve its search relevance.